The Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution: Difference between revisions

Sai95kamal (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (29 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==The Main Idea== | |||

In the context of the Kinetic Molecular Theory of Gases (KMToG), a gas has a large number of particles moving around with varying speeds, colliding with each other, causing changes in the speeds and directions of the particles. A good understanding of the properties of a gas requires the knowledge of the distribution of particles speeds. Named after James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann, the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution describes particle speeds in an idealized gas, in which the particles rarely interact with each other except for the brief collisions where energy and momentum are affected. The distribution of a particular gas depends on certain parameters, such as the Temperature of the system and mass of the gas particles. Certain properties of real gases inhibit their ability to be modeled by the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution so this distribution is best suited for application to ideal gases and certain rarefied gases at normal Temperatures. Knowledge of particle speeds given by this distribution is important to scientists performing reactions, because for a reaction to take place, particles must collide with sufficient energy to induce a transition state. This usually pertains to faster particles, so if the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution tells us how many particles have energies or speeds above a certain threshold, this is considered valuable information. | |||

===A Mathematical Model=== | |||

The Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution is the function: | |||

::<math> f(v) = \sqrt{\left(\frac{m}{2 \pi kT}\right)^3}\, 4\pi v^2 e^{- \frac{mv^2}{2kT}}</math>, where | |||

:::<math>m =</math> the mass of a particle | |||

:::<math>k =</math> Boltzmann's constant | |||

:::<math>T =</math> Thermodynamic Temperature | |||

:::<math>v =</math> the speed of the particle | |||

The probability that a molecule of a gas has a center-of-mass speed within the range <math>v</math> to <math>v+dv</math> is given by <math>f(v)dv</math>. | |||

As has been mentioned, the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution details the distribution of particle speeds in an ideal gas, and this distribution can be characterized in a few ways shown below: | |||

*The average speed, <math>v_{avg}</math>, is the sum of the speeds of all the particles divided by the number of particles in the volume of gas: | |||

:::<math> v_{avg} = \int_0^{\infty} v \, f(v) \, dv= \sqrt { \frac{8kT}{\pi m}}= \sqrt { \frac{8RT}{\pi M}}</math> | |||

::where ''R'' is the gas constant and ''M'' is the molar mass of the substance. | |||

*The most probable speed, <math>v_p</math>, is the speed associated with the highest point on the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution curve. Only a few particles will have this speed. To find this point on the distribution, we must calculate ''df/dv'', set it equal to zero, and then solve for ''v''. Then, we can ascertain: | |||

:::<math>v_p = \sqrt { \frac{2kT}{m} } = \sqrt { \frac{2RT}{M} }</math> | |||

*The root-mean-square speed, <math>v_{rms}</math>, is the square root of the average speed-squared and is given by: | |||

:::<math>v_{rms} = \left(\int_0^{\infty} v^2 \, f(v) \, dv \right)^{1/2}= \sqrt { \frac{3kT}{m}}= \sqrt { \frac{3RT}{M} } </math> | |||

If a gas is in thermal equilibrium and follows the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution, the following relation is always discovered: | |||

:::<math> v_p < v_{avg} < v_{rms} </math> | |||

===A Computational Model=== | |||

:'''Insert Computational Model here''' | |||

- | Maxwell-Boltzmann Distributions are not only represented by functions, but they are also represented by graphs. These graphs can tell scientists a lot about the properties of a gas. They can detail gas particles' masses and speeds, and the graphs can also tell a scientist how the gas responds to variations in temperature. | ||

: | To visualize how a Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution plot looks, the link below provides a demonstration to see how the Temperature of the system affects the particle speeds: | ||

*[http://www.absorblearning.com/media/attachment.action?quick=10w&att=2645 Maxwell-Boltzmann Temperature Effect Demo] | |||

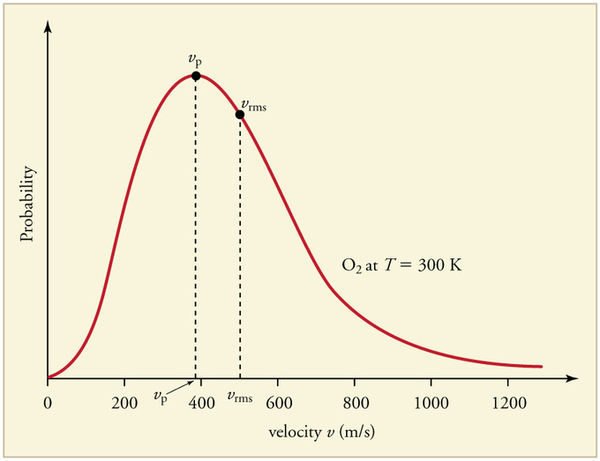

The graph below displays the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution of <math> O_2 </math> at 300 Kelvin. As one can see, the most probable speed, <math> v_p </math>, is marked at the peak of the distribution curve. The root-mean-square speed, <math> v_{rms} </math>, is also displayed on the curve. | |||

[[File: maxbolts.jpg|Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution of Oxygen at 300K|Source: chemwiki.ucdavis.edu|center|600px|center|thumb|Credit for this image is given to [http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Physical_Chemistry/Kinetics/Rate_Laws/Gas_Phase_Kinetics/Maxwell-Boltzmann_Distributions chemwiki.ucdavis.edu]]] | |||

==Examples== | |||

Below are three examples of how the Maxwell-Boltzmann equation is used and how to interpret the distribution graphs. | |||

===Simple=== | |||

Examine the given Maxwell-Boltzmann Distributions of Helium, Neon, Argon, and Xenon. | |||

[[File: Problem1.png|center|600px|thumb|Credit for this image is given to [http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Physical_Chemistry/Kinetics/Rate_Laws/Gas_Phase_Kinetics/Maxwell-Boltzmann_Distributions chemwiki.ucdavis.edu]]] | |||

:'''a) What can be said about the relationship between particle speed distributions and the mass of the particles?''' | |||

: | ::The Maxwell-Boltzmann distributions show a general trend with the mass of the particles: | ||

:::''As particle mass increases, the distribution of speeds becomes more localized around the most probable speed (<math>v_{p}</math>)'' | |||

::It is also worth noting heavier particles will have a lower average speed, as can be seen from the graph. | |||

===Middling=== | |||

:'''a) Looking at the graph above from the prior example and using some logic based on the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distributions, which will have a wider range of appreciable speeds:''' | |||

::''Helium at 500 K or Argon at 250 K?'' | |||

:::As we can see from the graph, Helium's distribution is much more spread out than Argon's when at the same Temperature. It is generally true that a particle's distribution will "flatten out" as the system's Temperature increases, as can see be seen in the demo in the Computational Model section. For us, this means Helium's distribution would become even more spread out compared to Argon's; it would have a much greater range of appreciable speeds than Argon. | |||

::''Helium at 300 K or Argon at 400 K?'' | |||

:::Even though Helium's Temperature is much less than Argon's, its much lighter particle mass still allows its distribution of speeds to have a larger appreciable range than Argon. | |||

::''Argon at 400 K or Argon at 900 K?'' | |||

:::In this case, both systems have Argon. Thus, the main characteristic to look at is the Temperature of each system. The higher Temperature system will have a larger range of speeds than the lower Temperature system.. | |||

===Difficult=== | |||

A sample of <math>100,000</math> Helium particles at <math>500°K</math> is in your possession. The mass of a Helium particle is <math>m_{helium} = 6.65 \times 10^{-27} \ kg </math> and Boltzmann's constant is <math>k = 1.381 \times 10^{-23} \left(\frac{m^2 \cdot kg}{s^2 \cdot K}\right)</math>. | |||

:'''a) What is the value of the Maxwell-Boltzmann function for the Helium particles at <math>325 \ \frac{m}{s}</math> | |||

::The Maxwell-Boltzmann function for Helium is: | |||

:::<math> f(v) = \sqrt{\left(\frac{m_{He}}{2 \pi kT}\right)^3}\, 4\pi v^2 e^{p(v)} </math>, where | |||

::::<math>p(v) = -\frac{m_{He}v^2}{2kT}</math> | |||

::Plugging in values for <math>f(325)</math> gives: | |||

:::<math>f(325) = \sqrt{\left(\frac{m_{He}}{2 \pi kT}\right)^3} 4\pi \ (325)^2 \ e^{p(325)} \quad \And \quad p(325) = -\frac{m_{He}(325)^2}{2kT}</math> | |||

:::<math>f(325) = \sqrt{\left(\frac{6.65 \times 10^{-27}}{2 \pi \times 1.381 \times 10^{-23} \times 500}\right)^3} 4\pi \ (325)^2 \ e^{p(325)} \quad \And \quad p(325) = -\frac{6.65 \times 10^{-27} \times (325)^2}{2 \times 1.381 \times 10^{-23} \times 500}</math> | |||

::Solving this gives: | |||

:::<math>f(325) = 8.1194 \times 10^{-5}</math> | |||

:'''b) About how many Helium particles are there at this speed?''' | |||

::The number of Helium particles at a speed of <math>325 \ \frac{m}{s}</math> <math>(N_{325})</math> is given by multiplying the value of the Maxwell-Boltzmann function at this value by the total number of Helium particles <math>(N_{total})</math>. This is because the value of the function is a probability of any Helium atom to be at that speed: | |||

:::<math>N_{325} = N_{total} \cdot f(325) = 8.1194</math> | |||

::Thus, we would think there are about <math>8</math> or <math>9</math> Helium particles in the sample at this speed. | |||

:'''c) How does <math>325 \ \frac{m}{s}</math> compare to the average speed of the Helium particles? The root mean squared speed? The most probable speed?''' | |||

::We will use the following three formulas to analytically answer this question: | |||

= | :::<math>v_{avg} = \sqrt{\frac{8kT}{\pi m}}</math> | ||

:::<math>v_{p} = \sqrt{\frac{2kT}{m}}</math> | |||

:::<math>v_{rms} = \sqrt{\frac{3kT}{m}}</math> | |||

::However, we can qualitatively answer this question also. Since there only about <math>8</math> or <math>9</math> Helium particles at such a low speed (for a gas), we can make an educated guess that the speed of <math>325 \ \frac{m}{s}</math> is much slower than any of the descriptive speeds of the distribution. We can reaffirm this qualitative answer by viewing the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution for Helium present in the Simple Example, where the most probable speed is about <math>1,100 \ \frac{m}{s}</math>. Furthermore, <math>500°K</math> is a pretty hot Temperature. In Fahrenheit it is about: | |||

:<math> | :::<math>°C = °K - 273.15 = 500 - 273.15 = 226.85°C</math> | ||

:::<math>°F = \left(\frac{9}{5}\right)(°C + 32) = \left(\frac{9}{5}\right)(226.85 + 32) = 465.93°F</math> | |||

::This is hotter than most ovens will ever be needed to be. | |||

: | ::Now, we will dive into finding the average speed, the most probable speed, and the root mean squared speed for the Helium distribution: | ||

:<math> | :::<math>v_{avg} = \sqrt{\frac{8 \times 1.381 \times 10^{-23} \times 500}{\pi \times 6.65 \times 10^{-27}}} = 1,626.1 \ \frac{m}{s}</math> | ||

: | :::<math>v_{p} = \sqrt{\frac{2 \times 1.381 \times 10^{-23} \times 500}{6.65 \times 10^{-27}}} = 1,441.1 \ \frac{m}{s}</math> | ||

:::<math>v_{rms} = \sqrt{\frac{3 \times 1.381 \times 10^{-23} \times 500}{6.65 \times 10^{-27}}} = 1,765.0 \ \frac{m}{s}</math> | |||

::As we can see, all these speeds are much greater than <math>325 \ \frac{m}{s}</math> | |||

==Connectedness== | ==Connectedness== | ||

This topic is particularly interesting to me because of its potential use in my father's work. My father is a | This topic is particularly interesting to me because of its potential use in my father's work. My father is a Chemist, and often he has to induce reactions involving gases. When I read about this topic, it was really interesting to see how one can calculate the speeds of particles based on these distributions. This is important because from this, one can calculate the energy of a single gas particle, and this could be important if a scientist like my father needed a specific energy level. It was really interesting to see how mass, speed, and the Temperature of a system all have important relationships with each other. This is not a huge connection to my major (Mechanical Engineering) as it seems to be more related to Chemical Engineering, but I would like to learn more about this concept in other classes. There are some applications for scientists to use these Maxwell-Boltzmann Distributions as guides to induce reactions between particles. | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

In 1857, a scientist by the name of Rudolf Clausius figured out how to calculate the speed of atoms. A few years later, in 1860, Irish physicist James Maxwell published a paper, in which he ascertained a way to connect the physical properties of gases to the distribution of particle velocities. His research compounded off of Clausius's work, but he went further by describing the distribution of speeds in reference to the average speed. In 1872, Austrian physicist, Ludwig Boltzmann, substantiated Maxwell's research by adding the H-theorem, which quantified the approach to equilibrium at which the Maxwell distribution velocities exist. Because of Maxwell and Boltzmann's collaboration, they had come up with a function called the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution. | |||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

===Further reading=== | ===Further reading=== | ||

*Matter and Interactions, Volume I, Modern Mechanics | |||

===External links=== | ===External links=== | ||

*http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Physical_Chemistry/Kinetics/Rate_Laws/Gas_Phase_Kinetics/Maxwell-Boltzmann_Distributions<br> | |||

*http://dwb.unl.edu/teacher/nsf/c09/c09links/www.kobold.demon.co.uk/kinetics/maxboltz.htm<br> | |||

*[[Thermal Energy]]<br> | |||

*[[First Law of Thermodynamics]]<br> | |||

*[[Second Law of Thermodynamics and Entropy]]<br> | |||

*[[Multi-particle analysis of Momentum]]<br> | |||

*[[Potential Energy of a Multiparticle System]]<br> | |||

*[[Work and Energy for an Extended System]]<br> | |||

==References== | |||

Blauch, D. (2014). Kinetic Molecular Theory. Retrieved December 5, 2015, from http://www.chm.davidson.edu/vce/kineticmoleculartheory/Maxwell.html | |||

Burton, T. (1999, April 25). The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. Retrieved December 5, 2015, from http://dwb.unl.edu/teacher/nsf/c09/c09links/www.kobold.demon.co.uk/kinetics/maxboltz.htm | |||

Chabay, R., & Sherwood, B. (2011). Entropy: Limits on the Possible. In Matter and Interactions (3rd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 839-842). Hoboken: Wiley. | |||

Maxwell-Boltzmann Distributions. (2013, October 2). Retrieved December 5, 2015, from http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Physical_Chemistry/Kinetics/Rate_Laws/Gas_Phase_Kinetics/Maxwell-Boltzmann_Distributions | |||

Search Results - Hmolpedia. (n.d.). Retrieved December 5, 2015, from http://www.eoht.info/page/Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution | |||

[ | Main Category: [http://www.physicsbook.gatech.edu/Main_Page Energy] | ||

Latest revision as of 23:16, 6 August 2019

The Main Idea

In the context of the Kinetic Molecular Theory of Gases (KMToG), a gas has a large number of particles moving around with varying speeds, colliding with each other, causing changes in the speeds and directions of the particles. A good understanding of the properties of a gas requires the knowledge of the distribution of particles speeds. Named after James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann, the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution describes particle speeds in an idealized gas, in which the particles rarely interact with each other except for the brief collisions where energy and momentum are affected. The distribution of a particular gas depends on certain parameters, such as the Temperature of the system and mass of the gas particles. Certain properties of real gases inhibit their ability to be modeled by the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution so this distribution is best suited for application to ideal gases and certain rarefied gases at normal Temperatures. Knowledge of particle speeds given by this distribution is important to scientists performing reactions, because for a reaction to take place, particles must collide with sufficient energy to induce a transition state. This usually pertains to faster particles, so if the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution tells us how many particles have energies or speeds above a certain threshold, this is considered valuable information.

A Mathematical Model

The Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution is the function:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(v) = \sqrt{\left(\frac{m}{2 \pi kT}\right)^3}\, 4\pi v^2 e^{- \frac{mv^2}{2kT}} }[/math], where

- [math]\displaystyle{ m = }[/math] the mass of a particle

- [math]\displaystyle{ k = }[/math] Boltzmann's constant

- [math]\displaystyle{ T = }[/math] Thermodynamic Temperature

- [math]\displaystyle{ v = }[/math] the speed of the particle

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(v) = \sqrt{\left(\frac{m}{2 \pi kT}\right)^3}\, 4\pi v^2 e^{- \frac{mv^2}{2kT}} }[/math], where

The probability that a molecule of a gas has a center-of-mass speed within the range [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ v+dv }[/math] is given by [math]\displaystyle{ f(v)dv }[/math].

As has been mentioned, the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution details the distribution of particle speeds in an ideal gas, and this distribution can be characterized in a few ways shown below:

- The average speed, [math]\displaystyle{ v_{avg} }[/math], is the sum of the speeds of all the particles divided by the number of particles in the volume of gas:

- [math]\displaystyle{ v_{avg} = \int_0^{\infty} v \, f(v) \, dv= \sqrt { \frac{8kT}{\pi m}}= \sqrt { \frac{8RT}{\pi M}} }[/math]

- where R is the gas constant and M is the molar mass of the substance.

- The most probable speed, [math]\displaystyle{ v_p }[/math], is the speed associated with the highest point on the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution curve. Only a few particles will have this speed. To find this point on the distribution, we must calculate df/dv, set it equal to zero, and then solve for v. Then, we can ascertain:

- [math]\displaystyle{ v_p = \sqrt { \frac{2kT}{m} } = \sqrt { \frac{2RT}{M} } }[/math]

- The root-mean-square speed, [math]\displaystyle{ v_{rms} }[/math], is the square root of the average speed-squared and is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ v_{rms} = \left(\int_0^{\infty} v^2 \, f(v) \, dv \right)^{1/2}= \sqrt { \frac{3kT}{m}}= \sqrt { \frac{3RT}{M} } }[/math]

If a gas is in thermal equilibrium and follows the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution, the following relation is always discovered:

- [math]\displaystyle{ v_p \lt v_{avg} \lt v_{rms} }[/math]

A Computational Model

- Insert Computational Model here

Maxwell-Boltzmann Distributions are not only represented by functions, but they are also represented by graphs. These graphs can tell scientists a lot about the properties of a gas. They can detail gas particles' masses and speeds, and the graphs can also tell a scientist how the gas responds to variations in temperature.

To visualize how a Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution plot looks, the link below provides a demonstration to see how the Temperature of the system affects the particle speeds:

The graph below displays the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution of [math]\displaystyle{ O_2 }[/math] at 300 Kelvin. As one can see, the most probable speed, [math]\displaystyle{ v_p }[/math], is marked at the peak of the distribution curve. The root-mean-square speed, [math]\displaystyle{ v_{rms} }[/math], is also displayed on the curve.

Examples

Below are three examples of how the Maxwell-Boltzmann equation is used and how to interpret the distribution graphs.

Simple

Examine the given Maxwell-Boltzmann Distributions of Helium, Neon, Argon, and Xenon.

- a) What can be said about the relationship between particle speed distributions and the mass of the particles?

- The Maxwell-Boltzmann distributions show a general trend with the mass of the particles:

- As particle mass increases, the distribution of speeds becomes more localized around the most probable speed ([math]\displaystyle{ v_{p} }[/math])

- It is also worth noting heavier particles will have a lower average speed, as can be seen from the graph.

Middling

- a) Looking at the graph above from the prior example and using some logic based on the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distributions, which will have a wider range of appreciable speeds:

- Helium at 500 K or Argon at 250 K?

- As we can see from the graph, Helium's distribution is much more spread out than Argon's when at the same Temperature. It is generally true that a particle's distribution will "flatten out" as the system's Temperature increases, as can see be seen in the demo in the Computational Model section. For us, this means Helium's distribution would become even more spread out compared to Argon's; it would have a much greater range of appreciable speeds than Argon.

- Helium at 300 K or Argon at 400 K?

- Even though Helium's Temperature is much less than Argon's, its much lighter particle mass still allows its distribution of speeds to have a larger appreciable range than Argon.

- Argon at 400 K or Argon at 900 K?

- In this case, both systems have Argon. Thus, the main characteristic to look at is the Temperature of each system. The higher Temperature system will have a larger range of speeds than the lower Temperature system..

Difficult

A sample of [math]\displaystyle{ 100,000 }[/math] Helium particles at [math]\displaystyle{ 500°K }[/math] is in your possession. The mass of a Helium particle is [math]\displaystyle{ m_{helium} = 6.65 \times 10^{-27} \ kg }[/math] and Boltzmann's constant is [math]\displaystyle{ k = 1.381 \times 10^{-23} \left(\frac{m^2 \cdot kg}{s^2 \cdot K}\right) }[/math].

- a) What is the value of the Maxwell-Boltzmann function for the Helium particles at [math]\displaystyle{ 325 \ \frac{m}{s} }[/math]

- The Maxwell-Boltzmann function for Helium is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(v) = \sqrt{\left(\frac{m_{He}}{2 \pi kT}\right)^3}\, 4\pi v^2 e^{p(v)} }[/math], where

- [math]\displaystyle{ p(v) = -\frac{m_{He}v^2}{2kT} }[/math]

- Plugging in values for [math]\displaystyle{ f(325) }[/math] gives:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(325) = \sqrt{\left(\frac{m_{He}}{2 \pi kT}\right)^3} 4\pi \ (325)^2 \ e^{p(325)} \quad \And \quad p(325) = -\frac{m_{He}(325)^2}{2kT} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(325) = \sqrt{\left(\frac{6.65 \times 10^{-27}}{2 \pi \times 1.381 \times 10^{-23} \times 500}\right)^3} 4\pi \ (325)^2 \ e^{p(325)} \quad \And \quad p(325) = -\frac{6.65 \times 10^{-27} \times (325)^2}{2 \times 1.381 \times 10^{-23} \times 500} }[/math]

- Solving this gives:

- [math]\displaystyle{ f(325) = 8.1194 \times 10^{-5} }[/math]

- b) About how many Helium particles are there at this speed?

- The number of Helium particles at a speed of [math]\displaystyle{ 325 \ \frac{m}{s} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ (N_{325}) }[/math] is given by multiplying the value of the Maxwell-Boltzmann function at this value by the total number of Helium particles [math]\displaystyle{ (N_{total}) }[/math]. This is because the value of the function is a probability of any Helium atom to be at that speed:

- [math]\displaystyle{ N_{325} = N_{total} \cdot f(325) = 8.1194 }[/math]

- Thus, we would think there are about [math]\displaystyle{ 8 }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ 9 }[/math] Helium particles in the sample at this speed.

- c) How does [math]\displaystyle{ 325 \ \frac{m}{s} }[/math] compare to the average speed of the Helium particles? The root mean squared speed? The most probable speed?

- We will use the following three formulas to analytically answer this question:

- [math]\displaystyle{ v_{avg} = \sqrt{\frac{8kT}{\pi m}} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ v_{p} = \sqrt{\frac{2kT}{m}} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ v_{rms} = \sqrt{\frac{3kT}{m}} }[/math]

- However, we can qualitatively answer this question also. Since there only about [math]\displaystyle{ 8 }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ 9 }[/math] Helium particles at such a low speed (for a gas), we can make an educated guess that the speed of [math]\displaystyle{ 325 \ \frac{m}{s} }[/math] is much slower than any of the descriptive speeds of the distribution. We can reaffirm this qualitative answer by viewing the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution for Helium present in the Simple Example, where the most probable speed is about [math]\displaystyle{ 1,100 \ \frac{m}{s} }[/math]. Furthermore, [math]\displaystyle{ 500°K }[/math] is a pretty hot Temperature. In Fahrenheit it is about:

- [math]\displaystyle{ °C = °K - 273.15 = 500 - 273.15 = 226.85°C }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ °F = \left(\frac{9}{5}\right)(°C + 32) = \left(\frac{9}{5}\right)(226.85 + 32) = 465.93°F }[/math]

- This is hotter than most ovens will ever be needed to be.

- Now, we will dive into finding the average speed, the most probable speed, and the root mean squared speed for the Helium distribution:

- [math]\displaystyle{ v_{avg} = \sqrt{\frac{8 \times 1.381 \times 10^{-23} \times 500}{\pi \times 6.65 \times 10^{-27}}} = 1,626.1 \ \frac{m}{s} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ v_{p} = \sqrt{\frac{2 \times 1.381 \times 10^{-23} \times 500}{6.65 \times 10^{-27}}} = 1,441.1 \ \frac{m}{s} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ v_{rms} = \sqrt{\frac{3 \times 1.381 \times 10^{-23} \times 500}{6.65 \times 10^{-27}}} = 1,765.0 \ \frac{m}{s} }[/math]

- As we can see, all these speeds are much greater than [math]\displaystyle{ 325 \ \frac{m}{s} }[/math]

Connectedness

This topic is particularly interesting to me because of its potential use in my father's work. My father is a Chemist, and often he has to induce reactions involving gases. When I read about this topic, it was really interesting to see how one can calculate the speeds of particles based on these distributions. This is important because from this, one can calculate the energy of a single gas particle, and this could be important if a scientist like my father needed a specific energy level. It was really interesting to see how mass, speed, and the Temperature of a system all have important relationships with each other. This is not a huge connection to my major (Mechanical Engineering) as it seems to be more related to Chemical Engineering, but I would like to learn more about this concept in other classes. There are some applications for scientists to use these Maxwell-Boltzmann Distributions as guides to induce reactions between particles.

History

In 1857, a scientist by the name of Rudolf Clausius figured out how to calculate the speed of atoms. A few years later, in 1860, Irish physicist James Maxwell published a paper, in which he ascertained a way to connect the physical properties of gases to the distribution of particle velocities. His research compounded off of Clausius's work, but he went further by describing the distribution of speeds in reference to the average speed. In 1872, Austrian physicist, Ludwig Boltzmann, substantiated Maxwell's research by adding the H-theorem, which quantified the approach to equilibrium at which the Maxwell distribution velocities exist. Because of Maxwell and Boltzmann's collaboration, they had come up with a function called the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution.

See also

Further reading

- Matter and Interactions, Volume I, Modern Mechanics

External links

- http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Physical_Chemistry/Kinetics/Rate_Laws/Gas_Phase_Kinetics/Maxwell-Boltzmann_Distributions

- http://dwb.unl.edu/teacher/nsf/c09/c09links/www.kobold.demon.co.uk/kinetics/maxboltz.htm

- Thermal Energy

- First Law of Thermodynamics

- Second Law of Thermodynamics and Entropy

- Multi-particle analysis of Momentum

- Potential Energy of a Multiparticle System

- Work and Energy for an Extended System

References

Blauch, D. (2014). Kinetic Molecular Theory. Retrieved December 5, 2015, from http://www.chm.davidson.edu/vce/kineticmoleculartheory/Maxwell.html

Burton, T. (1999, April 25). The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. Retrieved December 5, 2015, from http://dwb.unl.edu/teacher/nsf/c09/c09links/www.kobold.demon.co.uk/kinetics/maxboltz.htm

Chabay, R., & Sherwood, B. (2011). Entropy: Limits on the Possible. In Matter and Interactions (3rd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 839-842). Hoboken: Wiley.

Maxwell-Boltzmann Distributions. (2013, October 2). Retrieved December 5, 2015, from http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Physical_Chemistry/Kinetics/Rate_Laws/Gas_Phase_Kinetics/Maxwell-Boltzmann_Distributions

Search Results - Hmolpedia. (n.d.). Retrieved December 5, 2015, from http://www.eoht.info/page/Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution

Main Category: Energy