Charged Ring: Difference between revisions

m (→Connectedness) |

|||

| Line 174: | Line 174: | ||

The first known time when charged rings were utilized to describe electromagnetism was during Faraday’s discovery of electrical induction. To conduct his experiments, Faraday used a ring made of iron that was attached to a battery. When this makeshift circuit was turned on it manipulated a compass needle by deflecting it. He showcased an induced current in the ring. | The first known time when charged rings were utilized to describe electromagnetism was during Faraday’s discovery of electrical induction. To conduct his experiments, Faraday used a ring made of iron that was attached to a battery. When this makeshift circuit was turned on it manipulated a compass needle by deflecting it. He showcased an induced current in the ring. | ||

==Connectedness== | ===Connectedness=== | ||

Edited by AYESHA AHUJA Spring 2020 | Edited by AYESHA AHUJA Spring 2020 | ||

Revision as of 15:42, 5 May 2020

The Main Idea

Charges may be arranged in a variety of ways. When points are uniformly distributed a finite distance away from some point, which we define as the origin, we call this curve as a ring. We can position a Point Charge at every point upon this ring. To analyze this continuous arrangement of charges, we say that their individual contributions are infinitesimally small, and then sum each of these contributions together to arrive at the electric field produced by this charge distribution. We can compute the net electric field of this charge distribution with Coulomb's Law and by applying integration principles. The ring field can also be used to calculate the electric field of a Charged Disk.

A Mathematical Model

This mathematical model is based on the individual Electric Field contributions of a number of point charges, each of which is defined by

[math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{q}{|\vec{r}|^{2}}\hat{r} }[/math].

Do not forget this equation. This equation must be memorized as it isn't given on the formula sheet.

We also say that this vector field is a member of a linear space of vectors. This is to say that we can apply the Superposition Principle meaning that we can sum any number of these electric field vectors and obtain another vector which is the electric field vector contributed by those charges. When we continuously sum all of the vectors produced by these charges, we get the electric field produced by the entire arrangement of charges.

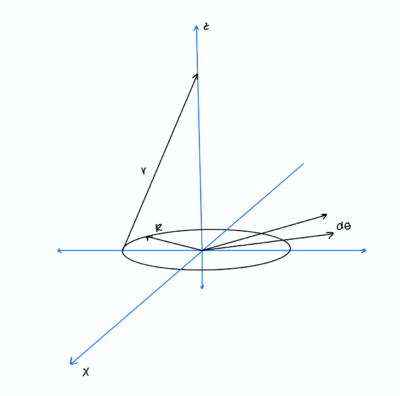

The diagram above shows the electric field due to one infinitesimal piece of the ring, [math]\displaystyle{ dq }[/math]. In order to avoid rigorous computations, we can see that the electric field of the charges cancels out in the vertical direction. Only the horizontal component will remain. For an observation location that is on the symmetry axis as the ring, the other two components will be zero. If the observation location were off axis, then it would be very different requiring more math. Since each piece, [math]\displaystyle{ dq }[/math], contributes a [math]\displaystyle{ d\vec{E} }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{dq}{|\vec{d}|^{2}}\hat{d} }[/math], we can compute the horizontal component by multiplying the magnitude of [math]\displaystyle{ d\vec{E} }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ \cos{θ} }[/math].

[math]\displaystyle{ |d\vec{E}_{z}| = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{dq}{r^2 + z^2}\cos{θ} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{dq}{r^2 + z^2}\frac{z}{(r^2 + z^2)^\frac{1}{2}} }[/math]

Now we integrate to sum all the electric field contributions of each infinitesimal [math]\displaystyle{ dq }[/math].

[math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E}_{z} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{z}{(r^2 + z^2)^\frac{3}{2}}\int_{}^{} dq = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{Qz}{(r^2 + z^2)^\frac{3}{2}} }[/math]

As a reminder, this is the equation given on the formula sheet. It only works when the location at which the field is being measured is along the [math]\displaystyle{ {z} }[/math] axis. However, the equation for it being off axis is not given on the equation sheet. That requires a separate and more difficult integration. Typically, the only way this would be asked on a test is to set up an equation that would be integrated that requires you to find a new [math]\displaystyle{ dQ }[/math].

Rigorous Derivation

1. Define shape characteristics of the ring

- The ring has some finite charge.

- We see that this arrangement is circular, so a coordinate system with which we can define radial and angular coordinates would be useful. Naturally, this would be the polar coordinate system.

- We also see that all charge is uniformly distributed some finite distance R from the center of the ring. It would be useful to let the center of the ring be the origin of our coordinate axes.

- Here is a reasonable arrangement for this charged ring.

- Since all charge is concentrated upon the edge of the circle, we can consider our charge distribution to be invariant with respect to radial distance. However, we do see that our charge distribution is the function of theta.

2. Compute charge distribution function

- Let us call the charge distribution as [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math]

- We have a charge distributed on the edge of the circle, so

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma=\frac{Q}{2\pi} }[/math]

- where [math]\displaystyle{ Q }[/math] represents the charge of the ring.

- What this equation means is that the charge is uniformly distributed along each unit of angular length. In this way, it is called angular charge density.

3. Compute infinitesimal charge contribution

- Let us consider an infinitesimal section of the ring which contains exactly one point charge. The dimension of this section is given by [math]\displaystyle{ d\theta }[/math] which is the infinitesimal angular size. So, the infinitesimal charge contribution, [math]\displaystyle{ dQ }[/math], is

- [math]\displaystyle{ dQ = \frac{Q}{2\pi}d\theta }[/math]

4. Compute infinitesimal electric field contribution

- Let us define some arbitrary location at which we are observing this ring of charge.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} = x\hat{x}+y\hat{y} + z\hat{z} }[/math]

- in polar coordinates, we see this becomes

- [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} = Rcos(\theta)\hat{x} + Rsin(\theta)\hat{y} + z\hat{z} }[/math].

- Recall that both sine and cosine are periodic with the period of [math]\displaystyle{ 2\pi }[/math]. This will become important later.

- The magnitude of this vector is

- [math]\displaystyle{ |\vec{r}| = \sqrt{R^{2}+z^{2}} }[/math]

- owing to the usage of the Pythagorean trigonometric identity.

- Now, we have what we need to write the electric field vector contributed by each piece of the ring of charge. Let this vector field piece be [math]\displaystyle{ d\vec{E} }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ d\vec{E}=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{q}{|\vec{r}|^{2}}\hat{r}=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{dQ}{(R^{2}+z^{2})^{3/2}}(Rcos(\theta)\hat{x}+Rsin(\theta)\hat{y}+z\hat{z}) }[/math]

5. Compute electric field vector

- So, now all that is left is to sum everything up. We are summing over the circumference of a circle, so our path is defined by [math]\displaystyle{ 0\leq\theta\leq 2\pi }[/math]. Let us now set up our integral.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E}=\int_{0}^{2\pi}\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{q}{|\vec{r}|^{2}}\hat{r} d\theta=\int_{0}^{2\pi}\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{Q}{2\pi(R^{2}+z^{2})^{3/2}}(Rcos(\theta)\hat{x}+Rsin(\theta)\hat{y}+z\hat{z})d\theta }[/math]

- Since both sine and cosine are [math]\displaystyle{ 2\pi }[/math] periodic functions, the [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] components of [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E} }[/math] go to [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{0} }[/math], which is very convenient. The result is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E}=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{Qz}{(z^{2}+R^{2})^{3/2}}\hat{z} }[/math].

Remark

If the path we are interested in is over a half circle, third-circle or quarter-circle, or indeed any circular section, simply adjust the bounds of integration and the charge density to the ones required by the curve of interest.

A Computational Model

This simulation shows the result of the computation for a ring composed of 2000 electrons. This is why the vector is pointing into the ring rather than out of the ring, which would happen for a ring composed of positively charged points.

Examples

Easy

1.) Find the function [math]\displaystyle{ E(x) }[/math] that represents the magnitude of the electric field along the center axis due to a uniformly charged ring of radius 0.04 m with total charge 8 C.

We can use the derived formula for the electric field due to a charged ring. Only the horizontal components of the electric field will remain as the rest will cancel out.

[math]\displaystyle{ E(x) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{(8 C)*x}{((0.04 m)^2 + x^2)^\frac{3}{2}} }[/math]

Middling

2.) A uniformly charged ring of radius 10.0 cm has a total charge of 91.0 µC. Find the electric field on the axis of the ring at the following distances from the center of the ring.

a. 1 cm

b. 5 cm

c. 30 cm

d. 100 cm

Use the derived formula, and convert the given distances into meters and the charge into Coulombs. Plug these into [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ E(x) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{Q*x}{(x^2 + R^2)^\frac{3}{2}} }[/math]

a. 8.069e6 N/C

b. 29.3e6 N/C

c. 7.76e6 N/C

d. 8.06e5 N/C

Difficult

Find the electric field at a distance [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] along the center axis away from a uniformly charged semicircular ring of radius R and total charge Q.

We can tweak the same integral for a uniformly charged ring by changing the limits of integration.

[math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E}=\int_{0}^{\pi}\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{q}{|\vec{r}|^{2}}\hat{r} d\theta=\int_{0}^{\pi}\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{Q}{\pi(R^{2}+z^{2})^{3/2}}(Rcos(\theta)\hat{x}+Rsin(\theta)\hat{y}+z\hat{z})d\theta }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\frac{Q}{\pi(R^{2}+z^{2})^{3/2}}(0\hat{x}+2R\hat{y}+{\pi}z\hat{z}) }[/math]

History

Added by AYESHA AHUJA SPRING 2020

The first known time when charged rings were utilized to describe electromagnetism was during Faraday’s discovery of electrical induction. To conduct his experiments, Faraday used a ring made of iron that was attached to a battery. When this makeshift circuit was turned on it manipulated a compass needle by deflecting it. He showcased an induced current in the ring.

Connectedness

Edited by AYESHA AHUJA Spring 2020

The idea of charge density is somewhat analogous to the idea of the mass density, which is useful in a variety of contexts, including the computation of the center of mass, the first and second moments of mass, which are useful in statics and rigid body dynamics. Instead of computing the uniform distribution of the mass of this ring, we are computing the uniform distribution of charge. This concept is also useful in visualizing what happens within a wire in a steady state circuit. The wire can be viewed to be a continuous length of rings of charge, which act as a channel through which electrons are transported, and that the electric field of these rings of charge pushes the electrons within the wire.

It is also important in the context of Maxwell's equations, specifically in Gauss's Law and in the Maxwell-Faraday equation, which are concerned with electron flux and induced fields, respectively.

See also

References

"Electric Field on the Axis of a Ring of Charge". University of Delaware Physics Library. Adapted from Stephen Kevan's lecture on Electric Fields and Charge Distribution. April 8, 1996. http://www.physics.udel.edu/~watson/phys208/exercises/kevan/efield1.html

Chabay, R., & Sherwood, B. (2015). Matter and Interactions (4th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 597-599). Wiley.

All images produced by the author

External Links

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=80mM3kSTZcE

http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/electric/elelin.html

http://www.physics.udel.edu/~watson/phys208/exercises/kevan/efield1.html