Mass: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(Wrote article) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Mass is one of the intrinsic properties of physical bodies that exist in 3-dimensional space. Mass is the measurement of the amount of matter a physical body possesses and is an underlying fundamental concept that governs other physical science concepts, such as [[Gravitational Force|gravity]], [[Inertia|inertia]], and [[Rest Mass Energy|rest energy]]. | |||

The SI units for mass is kilograms (kg), a base unit in the International System of Units. | |||

Mass | ==Defining Mass== | ||

One may differentiate between at least seven different aspects of mass, or seven distinct physical approaches to relating mass.<sup>[[#References|1]]</sup><!-- <ref name="Rindler2">{{cite book |author=W. Rindler |date=2006 |title=Relativity: Special, General, And Cosmological |url=https://books.google.com/?id=MuuaG5HXOGEC&pg=PA16 |pages=16–18 |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |isbn=0-19-856731-6}}</ref> --> However, there exists some constant that unifies all widely accepted concepts related to mass. Below are some of these concepts. | |||

=== | ===Inertial Mass=== | ||

'''Main article: [[Inertia]]''' | |||

Inertial mass is the measure of some physical body's resistance to changes in motion (the definition of [[Inertia|inertia]]). A physical body's motional resistance is inversely proportional to its inertial mass. Put more simply, under the same force <math>F</math>, a body with mass <math>m</math> will experience greater [[Velocity#Acceleration|acceleration]] than that of a body with mass <math>M</math>, when <math>m < M</math>. | |||

=== | ===Gravitational Mass=== | ||

'See also: [[Gravitational Force]]'' | |||

====Active Gravitational Mass==== | |||

Active gravitational mass is the measure of the magnitude of a body's gravitational field at corresponding distances. When other bodies of mass are involved, active gravitational mass may be defined as the [[Gravitational Force|gravitational force]] that other bodies experience at corresponding distances. For surfaces, active gravitational mass may be more formally defined as the measure of a body's [[Gravitational flux|gravitational flux]]. Qualitatively speaking, this just means active gravitational mass determines how strong a body's gravitational field is. A body's active gravitational mass can be demonstrated by allowing a second, smaller test body to free-fall and then measuring the [[Velocity#Acceleration|acceleration]] that the second body experiences. In classical mechanics, this can formally be shown as | |||

::<math>\mathbf{g}=\frac{\mathbf{F}}{m}=-\frac{{\rm d}^2\mathbf{r}}{{\rm d}t^2}=-Gm\frac{\mathbf{\hat{r}}}{|\mathbf{r}|^2},</math> | |||

:where | |||

::'''g''' is the gravitational acceleration caused by active gravitational mass's resulting gravitational field | |||

::'''F''' is the gravitational force on a test body | |||

::'''m''' is the mass of a test body | |||

::'''r''' is the direction vector from the body being measured to the test body | |||

::'''t''' is time | |||

::'''G''' is the universal gravitational constant (<math>6.6740831 \times 10^{-11} {\rm \ N \ m^{2} \ kg^{-2} }</math>) | |||

== | ====Passive Gravitational Mass==== | ||

Passive gravitational mass is the measure of how affected an body is by a gravitational field. When the sole force acting on a physical body is a result of its interaction with a gravitational field, passive gravitational mass of a body can be calculated by the formula | |||

::<math>\mathbf{F} = ma</math>. | |||

:Algebraically solving for '''m''' gives: | |||

::<math>m = \frac{\mathbf{F}}{a}</math> | |||

:where | |||

::* ''F'' is the body's weight in the given | |||

::* ''m'' is the body's passive gravitational mass | |||

::* ''a'' is the free-fall acceleration of the body. | |||

===Gravitational | ====Combining the Gravitational Masses==== | ||

The differentiation between active and passive gravitational masses can be bridged by combining the two equations derived above and [[Newton's Third Law of Motion]], which results in the general gravitational force equation | |||

::<math>|\vec{\mathbf{F}}_{grav}|= G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}\</math>, | |||

:or in vector form | |||

::<math>\vec{\mathbf{F}}_{grav}= -G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}\ </math><math>\mathbf{\hat{r}}</math>. | |||

== | ===Rest Energy of Mass=== | ||

'Main article: [[Rest Mass Energy]]'' | |||

The mass-energy equivalence states that there exists an intrinsic energy quantity equivalent for any quantity of mass, even when the body of mass has no other form of energy (no [[Kinetic Energy|kinetic]], [[Potential Energy|potential]], elastic, chemical, thermal, or otherwise) and vice versa. This was made famous by Albert Einstein's equation | |||

::<math>E_rest = mc^2</math> | |||

:where | |||

::''E<sub>rest</sub>' is the rest energy of a body of mass | |||

::''m'' is the mass of the body | |||

::''c'' is the speed of light (approximately <math>3.00 \times 10^{8} {\rm \ m/s}</math> in a vacuum) | |||

This phenomenon can be observed in many processes, including nuclear fusion (the Sun) and the gravitational bending of light. | |||

=== | ===Deformation of Spacetime=== | ||

''See also: [[Einstein's Theory of Special Relativity]]'' | |||

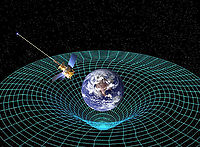

[[ Image:SpacetimeCurvature.jpg | thumb | right | 200px | A 3-D visualization of the planet Earth deforming spacetime. Credit to NASA for the image. ]] | |||

The deformation of spacetime is a relativistic phenomenon that is the result of the existence of mass.[[#References|2]] The manifestation of the deformation of spacetime can be seen with gravitational time dilation. For example, given two hypothetical, isolated bodies of mass '''Small''' and '''Large''' where the masses <math>M_{Small} << M_{Large}</math>, an observer near '''Small''' will observe the passage of time much slower relative to an observer near '''Large'''. In popular culture, Christopher Nolan's science fiction film ''Interstellar'' depicted this phenomenon when astronauts Joe Cooper, Amelia Brand, and Dr. Doyle approach the supermassive black hole Gargantua, while scientist Dr. Romilly remains further from the black hole's spacetime deformation. As a result, in the movie, for every hour the characters Cooper, Brand, and Doyle remain close to the black hole's huge mass and deformation of spacetime, Romilly observes the passage of 23 years of time. | |||

== | ===Quantum Mass=== | ||

==Differentiating between Mass and Weight== | |||

In everyday usage, the terms "mass" and "weight" are often interchanged incorrectly. For example, one may state that they weigh 100 kg, even though kilograms is a unit of mass, not weight. Because the majority of humans exist on Earth, where the gravitational field is essentially constant, mass and weight are proportional, so the distinction can be overlooked. However, inconsistencies occur when the gravitational fields are difference. For instance, the mass of a person on both Earth and the Moon will be the same, whereas the weight of a person on Earth and the Moon will be different. This is because weight is actually a measurement of force (typically [[Gravitational Force|gravitational]]) exerted on a body of mass. The equation <math>\mathbf{F} = ma</math> reappears again to describe weight, where '''F''' is an object's weight, ''m'' is the object's mass, and ''a'' is the body's free-fall [[Velocity#Acceleration|acceleration]]. | |||

==History== | |||

=== | ===Pre-Newtonian Concepts=== | ||

The idea about the "amount" of something and its relationship to weight predates recorded history. Humans, at some early prehistoric time, recognized the weight of a group of objects and its direct proportionality to the number of objects in the group. The most direct and widely supported evidence of this is the discovery of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weighing_scale weighing scales] in early civilization trade. However, there exists no evidence that any of these civilizations recognized the [[#Mass versus Weight|distinction between mass and weight]], since the effects of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gravity_of_Earth Earth's gravity] near the surface ensures that the weight and mass of an object are directly proportional. | |||

== See also == | |||

* [[Kinds of Matter]] | |||

== | * [[Gravitational Force]] | ||

* [[Inertia]] | |||

* [[Rest Mass Energy]] | |||

* [[Sir Isaac Newton]] | |||

* [[Einstein's Theory of Special Relativity]] | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<!-- If MediaWiki has citations installed proper, uncomment all ref tags, and put this here: {{Reflist|30em}} --> | |||

# W. Rindler (2006). Relativity: Special, General, And Cosmological. Oxford University Press. pp. 16–18. ISBN 0-19-856731-6. | |||

# A. Einstein, "Relativity : the Special and General Theory by Albert Einstein." Project Gutenberg. <https://www.gutenberg.org/etext/5001.> | |||

[[Category: | [[Category:Properties of Matter]] | ||

Revision as of 23:52, 4 December 2015

Mass is one of the intrinsic properties of physical bodies that exist in 3-dimensional space. Mass is the measurement of the amount of matter a physical body possesses and is an underlying fundamental concept that governs other physical science concepts, such as gravity, inertia, and rest energy.

The SI units for mass is kilograms (kg), a base unit in the International System of Units.

Defining Mass

One may differentiate between at least seven different aspects of mass, or seven distinct physical approaches to relating mass.1 However, there exists some constant that unifies all widely accepted concepts related to mass. Below are some of these concepts.

Inertial Mass

Main article: Inertia

Inertial mass is the measure of some physical body's resistance to changes in motion (the definition of inertia). A physical body's motional resistance is inversely proportional to its inertial mass. Put more simply, under the same force [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math], a body with mass [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] will experience greater acceleration than that of a body with mass [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math], when [math]\displaystyle{ m \lt M }[/math].

Gravitational Mass

'See also: Gravitational Force

Active Gravitational Mass

Active gravitational mass is the measure of the magnitude of a body's gravitational field at corresponding distances. When other bodies of mass are involved, active gravitational mass may be defined as the gravitational force that other bodies experience at corresponding distances. For surfaces, active gravitational mass may be more formally defined as the measure of a body's gravitational flux. Qualitatively speaking, this just means active gravitational mass determines how strong a body's gravitational field is. A body's active gravitational mass can be demonstrated by allowing a second, smaller test body to free-fall and then measuring the acceleration that the second body experiences. In classical mechanics, this can formally be shown as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{g}=\frac{\mathbf{F}}{m}=-\frac{{\rm d}^2\mathbf{r}}{{\rm d}t^2}=-Gm\frac{\mathbf{\hat{r}}}{|\mathbf{r}|^2}, }[/math]

- where

- g is the gravitational acceleration caused by active gravitational mass's resulting gravitational field

- F is the gravitational force on a test body

- m is the mass of a test body

- r is the direction vector from the body being measured to the test body

- t is time

- G is the universal gravitational constant ([math]\displaystyle{ 6.6740831 \times 10^{-11} {\rm \ N \ m^{2} \ kg^{-2} } }[/math])

Passive Gravitational Mass

Passive gravitational mass is the measure of how affected an body is by a gravitational field. When the sole force acting on a physical body is a result of its interaction with a gravitational field, passive gravitational mass of a body can be calculated by the formula

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{F} = ma }[/math].

- Algebraically solving for m gives:

- [math]\displaystyle{ m = \frac{\mathbf{F}}{a} }[/math]

- where

- F is the body's weight in the given

- m is the body's passive gravitational mass

- a is the free-fall acceleration of the body.

Combining the Gravitational Masses

The differentiation between active and passive gravitational masses can be bridged by combining the two equations derived above and Newton's Third Law of Motion, which results in the general gravitational force equation

- [math]\displaystyle{ |\vec{\mathbf{F}}_{grav}|= G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}\ }[/math],

- or in vector form

- [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{\mathbf{F}}_{grav}= -G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}\ }[/math][math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{\hat{r}} }[/math].

Rest Energy of Mass

'Main article: Rest Mass Energy The mass-energy equivalence states that there exists an intrinsic energy quantity equivalent for any quantity of mass, even when the body of mass has no other form of energy (no kinetic, potential, elastic, chemical, thermal, or otherwise) and vice versa. This was made famous by Albert Einstein's equation

- [math]\displaystyle{ E_rest = mc^2 }[/math]

- where

- Erest' is the rest energy of a body of mass

- m is the mass of the body

- c is the speed of light (approximately [math]\displaystyle{ 3.00 \times 10^{8} {\rm \ m/s} }[/math] in a vacuum)

This phenomenon can be observed in many processes, including nuclear fusion (the Sun) and the gravitational bending of light.

Deformation of Spacetime

See also: Einstein's Theory of Special Relativity

The deformation of spacetime is a relativistic phenomenon that is the result of the existence of mass.2 The manifestation of the deformation of spacetime can be seen with gravitational time dilation. For example, given two hypothetical, isolated bodies of mass Small and Large where the masses [math]\displaystyle{ M_{Small} \lt \lt M_{Large} }[/math], an observer near Small will observe the passage of time much slower relative to an observer near Large. In popular culture, Christopher Nolan's science fiction film Interstellar depicted this phenomenon when astronauts Joe Cooper, Amelia Brand, and Dr. Doyle approach the supermassive black hole Gargantua, while scientist Dr. Romilly remains further from the black hole's spacetime deformation. As a result, in the movie, for every hour the characters Cooper, Brand, and Doyle remain close to the black hole's huge mass and deformation of spacetime, Romilly observes the passage of 23 years of time.

Quantum Mass

Differentiating between Mass and Weight

In everyday usage, the terms "mass" and "weight" are often interchanged incorrectly. For example, one may state that they weigh 100 kg, even though kilograms is a unit of mass, not weight. Because the majority of humans exist on Earth, where the gravitational field is essentially constant, mass and weight are proportional, so the distinction can be overlooked. However, inconsistencies occur when the gravitational fields are difference. For instance, the mass of a person on both Earth and the Moon will be the same, whereas the weight of a person on Earth and the Moon will be different. This is because weight is actually a measurement of force (typically gravitational) exerted on a body of mass. The equation [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{F} = ma }[/math] reappears again to describe weight, where F is an object's weight, m is the object's mass, and a is the body's free-fall acceleration.

History

Pre-Newtonian Concepts

The idea about the "amount" of something and its relationship to weight predates recorded history. Humans, at some early prehistoric time, recognized the weight of a group of objects and its direct proportionality to the number of objects in the group. The most direct and widely supported evidence of this is the discovery of weighing scales in early civilization trade. However, there exists no evidence that any of these civilizations recognized the distinction between mass and weight, since the effects of Earth's gravity near the surface ensures that the weight and mass of an object are directly proportional.

See also

- Kinds of Matter

- Gravitational Force

- Inertia

- Rest Mass Energy

- Sir Isaac Newton

- Einstein's Theory of Special Relativity

References

- W. Rindler (2006). Relativity: Special, General, And Cosmological. Oxford University Press. pp. 16–18. ISBN 0-19-856731-6.

- A. Einstein, "Relativity : the Special and General Theory by Albert Einstein." Project Gutenberg. <https://www.gutenberg.org/etext/5001.>