Steady State: Difference between revisions

Nfortingo3 (talk | contribs) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''claimed by | '''claimed by Amira Abadir (Fall 2016)''' | ||

claimed by Nyemkuna Fortingo ( Spring 2016) | |||

claimed by Shirin Kale (Fall 2015) | claimed by Shirin Kale (Fall 2015) | ||

Revision as of 18:29, 31 October 2016

claimed by Amira Abadir (Fall 2016) claimed by Nyemkuna Fortingo ( Spring 2016) claimed by Shirin Kale (Fall 2015)

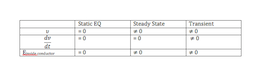

Steady state is the term used to describe an assembled circuit in which the current and net electric field are constant and stay approximately constant for a very long time. Circuits with uniform thickness and composition can be described as steady state if charged particles move with constant current in each section of a wire in the circuit. Circuits in the steady state do not change current as a function of time.

The Main Idea

After a circuit has been assembled, it can be described as steady state if it meets the following requirements:

- mobile charges are moving with constant drift velocity anywhere in the circuit

- no excess charges accumulate anywhere in the circuit

Although mobile charges are moving, the drift velocities of the charges do not vary with time at any location in the circuit and thus, the current is constant throughout the circuit. However, since current is also a function of the cross-sectional area and charge density (composition) of the wire - as shown by the equation for conventional current below - a steady state circuit is more specifically described as one in which the current is constant in each section of a wire with uniform thickness and composition.

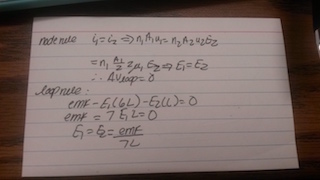

A Mathematical Model

i = electron current

I = conventional current

v = drift speed

q = charge of mobile particles

A = cross-sectional area of wire

In the steady state, at each section of circuit:

A Conceptual Understanding

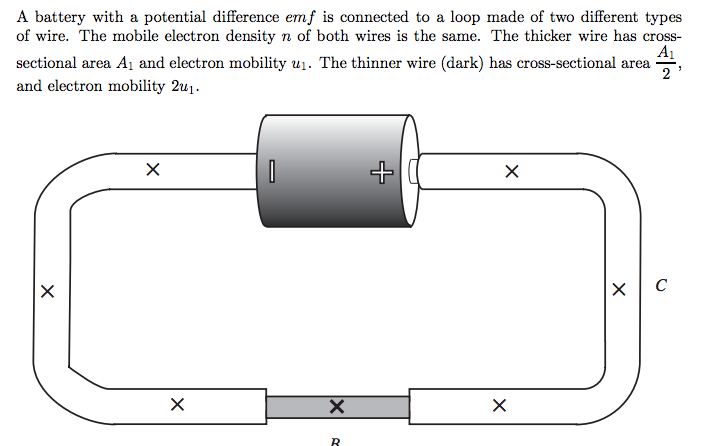

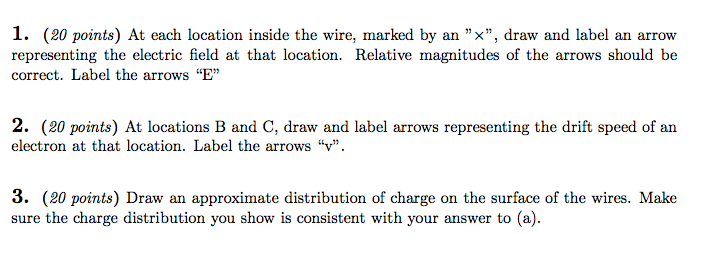

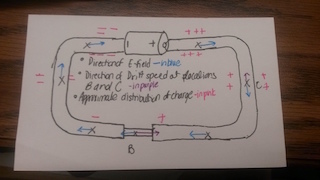

Because mobile charges are moving (with constant drift speed) in the circuit, there must be an applied electric field inside the wire that causes the mobile charges to move. Since there is no excess charge inside the wire, the electric field must be produced from surface charges. And because this electric field is responsible for moving the mobile charges inside the wire, the direction of the electric field at each location in the wire must be parallel to the wire.

Once a circuit is described as being in the steady state, there are three things we know to be true. It is true that:

- there must be a nonzero electric field in the wire

- the electric field has uniform magnitude throughout the wire

- the electric field is parallel to the wire at every location along the wire

The electric field and current inside the wire remains constant because the electric force (F = qE) acting on the mobile charged particles and allowing them to move through the circuit is canceled out by the drag force produced by the moving charged particles such that the net force is zero and thus, acceleration is zero.

When you assume that a circuit is in steady state, you are basically assuming that the circuit has been assembled and connected for a long time (such that the current is constant). However, there is a process that occurs - when the circuit is first assembled - before the circuit reaches steady state. Let’s take a look at some examples to better understand steady state circuits.

Examples

Simple

Middling

Difficult

Connectedness

As a biomedical engineer, the idea of steady state circuits is surprisingly interesting to me because the process of reaching steady state in a circuit is much like the process of maintaining homeostasis in the human body.

In the field of biochemistry, steady state can be related to cells. In ionic steady state, cells maintain different internal and external concentrations of various ionic species with the cell.. If the cells are not in steady state, this means there is equilibrium. With steady state, there is not an equilibrium establishes meaning both the inner and outer cell are never equal in concentration. There are continuous ions moving within and out of the cell.

See also

- Circuit Components

- RC Circuits

- Thin and Thick Wires

- Node Rule

- Loop Rule

- Ohm's Law

- Series Circuits

- Parallel Circuits

References

Matter and Interactions Vol. II http://people.seas.harvard.edu/~jones/es154/pages/nicetut/book2/RC.html http://ocw.mit.edu/high-school/physics/exam-prep/electric-circuits/steady-state-direct-current-circuits-batteries-resistors/8_02_spring_2007_chap7dc_circuits.pdf

Chabay, Ruth W., and Bruce A. Sherwood. "18." Matter & Interactions. N.p.: n.p., n.d. N. pag. Print.