Field of a Charged Rod: Difference between revisions

Parkercoye (talk | contribs) |

Parkercoye (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

=== A Mathematical Model === | === A Mathematical Model === | ||

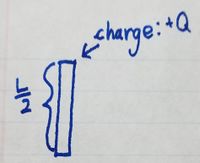

The process of calculating a uniformly charged rod's electric field is tedious, but breaking the process down into several steps makes the task at hand easier. Consider a uniformly charged thin rod of length <math>L</math> and positive charge <math>Q</math> centered on and lying along the x-axis. The rod is being observed from above at a point on the y-axis. | |||

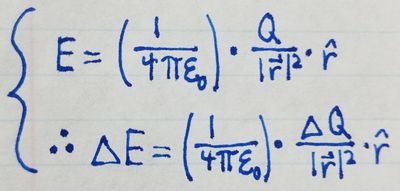

'''Step 1: Divide the Distribution into Pieces; Draw <math>\Delta \vec{E}</math>''' | |||

Imagine dividing the rod into a series of very thin slices, each with the same charge <math>\Delta Q</math>. This charge <math>\Delta Q</math> is a small part of the overall charge. Picture it as a point charge. Each slice contributes its own electric field, <math>\Delta E</math>. Summing all these individual slices of <math>E</math> gives you the total electric field of the rod. This process is the same as taking an integral, as each thickness approaches 0 and the the number of slices approaches infinity. Note that in this example, the variable that is changing for each slice is its x-coordinate. | |||

'''Step 2: Write an Expression for the Electric Field Due to One Piece''' | |||

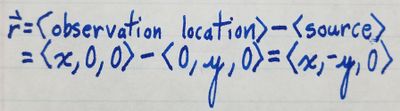

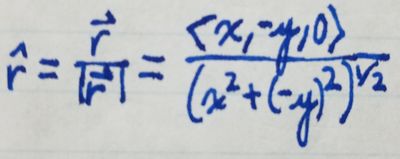

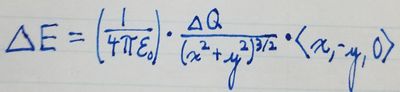

The second step is to write a mathematical expression for the field <math>\Delta E</math> contributed by a single slice of the rod. We use the formula of the electric field for a point charge because we are imagining each slice as a point charge. First, determine <math>r</math>, the vector pointing from the source to the observation location. For our example, this is <math> r = obs - source = <0,y,0> - < x,0,0> = <-x,y,0></math>. Now use this to calculate the magnitude and direction of <math>r</math>. So <math>|\vec{r}| = \sqrt{(-x)^2 + y^2} = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}</math> and <math>\hat{r} = \frac{\vec{r}}{\hat{r}} = \frac{< -x,y,0>}{\sqrt{x^2 + y^2}} </math>. <math> \hat{r}</math> is the vector portion of the expression for the field. The scalar portion is <math> \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{\Delta Q}{|\vec{r}|^2}</math>. Thus the expression for one slice of the rod is: | |||

<math> \Delta \vec{E} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{\Delta Q}{(\sqrt{x^2+y^2})^{3/2}} \cdot < -x,y,0> </math>. | |||

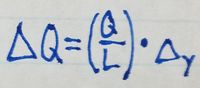

'''Determining <math>\Delta Q</math> and the integration variable''' | |||

In the first step, we determined that the changing variable for this rod was its x-coordinate. This means the integration variable is <math> dx</math>. We need to put this integration variable into our expression for the electric field. More specifically, we need to express <math>\Delta Q</math> in terms of the integration variable. Recall that the rod is uniformly charged, so the charge on any single slice of it is: <math> | |||

\Delta Q = (\frac{\Delta x}{L})\cdot Q</math>. This quantity can also be expressed in terms of the charge density. | |||

'''Expression for <math> \Delta \vec{E}</math> | |||

Substitute the expression for the integration variable into the formula for the electric field of one slice. Separating the equation into separate x and y components, we get <math> \Delta \vec{E_x} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{Q}{L} \cdot \frac{-x}{(\sqrt{x^2+y^2})^{3/2}} \cdot dx </math> and <math> \Delta \vec{E_y} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{Q}{L} \cdot \frac{y}{(\sqrt{x^2+y^2})^{3/2}} \cdot dx </math>. Note that we have replaced <math> \Delta x </math> with <math> dx</math> in preparation for integration. | |||

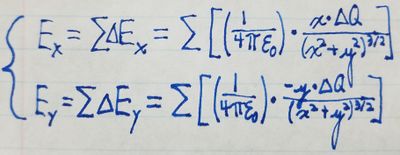

'''Step 3: Add Up the Contributions of All the Pieces''' | |||

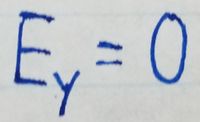

The third step is to sum all of our slices. We can go about this in two ways. One way is with numerical summation, or separating the object into a finite number of small pieces, calculating the individual contributing electric fields, and then summing them. Another, more precise method is to integrate. Most of the work of finding the field of a uniformly charged object is setting up this integral. If you have reached the correct expression to integrate, the rest is simple math. The bounds for integration are the coordinates of the start and stop of the rod. In this example the bounds are from <math>-L/2</math> to <math>+L/2</math>. So the expression is <math> \int\limits_{-L/2}^{L/2}\ \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{Q}{L} \cdot \frac{y}{(\sqrt{x^2+y^2})^{3/2}} \cdot dx. </math> Solving this gives the final expression <math> E_y = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{Q}{x} \cdot \frac{1}{(\sqrt{x^2+ (L/2)^2})} </math>. Note that the field parallel to the x axis is zero. This can be observed due to the symmetry of the problem. | |||

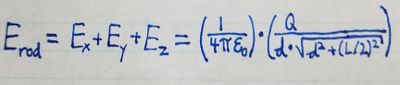

This equation can be written more generally as <math> E = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{Q}{r} \cdot \frac{1}{(\sqrt{r^2+ (L/2)^2})} </math> where r represents the distance from the rod to the observation location. | |||

'''Step 4:Checking the Result''' | |||

Finally, the fourth step is to check the result. The units should be the same as the units of the expression for the electric field for a single point particle <math> E = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{Q}{r^2} </math>. | |||

Our answer has the right units, since <math> \frac{1}{(\sqrt{x^2+ (L/2)^2})} </math>. has the same units of <math>\frac{Q}{r^2}</math> | |||

Is the direction qualitatively correct? We have the electric field pointing straight away from the midpoint of the rod, which is correct, given the symmetry of the situation. The vertical component of the electric field should indeed be zero. | |||

==== The System in Question ==== | ==== The System in Question ==== | ||

Revision as of 11:11, 20 August 2019

(After finishing this, I found an article called Charged Rod written by the people of yesteryear. I didn't see that and created this new one instead. The 2 should be merged in the future.)

The Main Idea

Previously, we've learned about the electric field of a point particle. Often, when analyzing physical systems, it is the case that we're unable to analyze each individual particle that composes an object and need to therefore generalize collections of particles into shapes (in this case, a rod) whereby the mathematics corresponding to electric field calculations can be simplified. This can essentially be done by adding up the contributions to the electric field made by parts of an object, approximating each part of an object as a point charge.

Some objects, such as rods, can be modeled as a uniformly charged object in order to calculate the electric field at some observation location. The following wiki page provides an overview of electric fields created by uniformly charged thin rods, briefly presenting its inception, some specific cases, and proof of concept experiments. The case of a uniformly charged thin rod is a fundamental example of electric field patterns and calculations within physics. Its implications can be applied to other charged objects, such as rings, disks, and spheres.

In practical situations, objects have charges spread all over their surface. When going about calculating the electric fields of these objects, we can either use one of two processes: numerical summation or integration, or dividing an object into many pieces and summing the individual pieces' electric field contributions. As with point charges, the direction of the field is determined by the sign of the object's charge (positive-points away, negative-points toward) and the size of the field is determined by the observation distance and the magnitude of the object's charge.

The process of finding the electric field due to charge distributed over an object has four steps:

1. Divide the charged object into small pieces. Make a diagram and draw the electric field [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta \vec{E} }[/math] contributed by one of the pieces.

2. Choose an origin and the axes. Write an algebraic expression for the electric field [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta \vec{E} }[/math] due to one piece.

3. Add up the contributions of all pieces, either numerically or symbolically.

4. Check that the result is physically correct.

A Mathematical Model

The process of calculating a uniformly charged rod's electric field is tedious, but breaking the process down into several steps makes the task at hand easier. Consider a uniformly charged thin rod of length [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] and positive charge [math]\displaystyle{ Q }[/math] centered on and lying along the x-axis. The rod is being observed from above at a point on the y-axis.

Step 1: Divide the Distribution into Pieces; Draw [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta \vec{E} }[/math]

Imagine dividing the rod into a series of very thin slices, each with the same charge [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta Q }[/math]. This charge [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta Q }[/math] is a small part of the overall charge. Picture it as a point charge. Each slice contributes its own electric field, [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta E }[/math]. Summing all these individual slices of [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] gives you the total electric field of the rod. This process is the same as taking an integral, as each thickness approaches 0 and the the number of slices approaches infinity. Note that in this example, the variable that is changing for each slice is its x-coordinate.

Step 2: Write an Expression for the Electric Field Due to One Piece

The second step is to write a mathematical expression for the field [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta E }[/math] contributed by a single slice of the rod. We use the formula of the electric field for a point charge because we are imagining each slice as a point charge. First, determine [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math], the vector pointing from the source to the observation location. For our example, this is [math]\displaystyle{ r = obs - source = \lt 0,y,0\gt - \lt x,0,0\gt = \lt -x,y,0\gt }[/math]. Now use this to calculate the magnitude and direction of [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math]. So [math]\displaystyle{ |\vec{r}| = \sqrt{(-x)^2 + y^2} = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{r} = \frac{\vec{r}}{\hat{r}} = \frac{\lt -x,y,0\gt }{\sqrt{x^2 + y^2}} }[/math]. [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{r} }[/math] is the vector portion of the expression for the field. The scalar portion is [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{\Delta Q}{|\vec{r}|^2} }[/math]. Thus the expression for one slice of the rod is: [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta \vec{E} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{\Delta Q}{(\sqrt{x^2+y^2})^{3/2}} \cdot \lt -x,y,0\gt }[/math].

Determining [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta Q }[/math] and the integration variable

In the first step, we determined that the changing variable for this rod was its x-coordinate. This means the integration variable is [math]\displaystyle{ dx }[/math]. We need to put this integration variable into our expression for the electric field. More specifically, we need to express [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta Q }[/math] in terms of the integration variable. Recall that the rod is uniformly charged, so the charge on any single slice of it is: [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta Q = (\frac{\Delta x}{L})\cdot Q }[/math]. This quantity can also be expressed in terms of the charge density.

Expression for [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta \vec{E} }[/math]

Substitute the expression for the integration variable into the formula for the electric field of one slice. Separating the equation into separate x and y components, we get [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta \vec{E_x} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{Q}{L} \cdot \frac{-x}{(\sqrt{x^2+y^2})^{3/2}} \cdot dx }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta \vec{E_y} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{Q}{L} \cdot \frac{y}{(\sqrt{x^2+y^2})^{3/2}} \cdot dx }[/math]. Note that we have replaced [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta x }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ dx }[/math] in preparation for integration.

Step 3: Add Up the Contributions of All the Pieces

The third step is to sum all of our slices. We can go about this in two ways. One way is with numerical summation, or separating the object into a finite number of small pieces, calculating the individual contributing electric fields, and then summing them. Another, more precise method is to integrate. Most of the work of finding the field of a uniformly charged object is setting up this integral. If you have reached the correct expression to integrate, the rest is simple math. The bounds for integration are the coordinates of the start and stop of the rod. In this example the bounds are from [math]\displaystyle{ -L/2 }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ +L/2 }[/math]. So the expression is [math]\displaystyle{ \int\limits_{-L/2}^{L/2}\ \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{Q}{L} \cdot \frac{y}{(\sqrt{x^2+y^2})^{3/2}} \cdot dx. }[/math] Solving this gives the final expression [math]\displaystyle{ E_y = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{Q}{x} \cdot \frac{1}{(\sqrt{x^2+ (L/2)^2})} }[/math]. Note that the field parallel to the x axis is zero. This can be observed due to the symmetry of the problem. This equation can be written more generally as [math]\displaystyle{ E = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{Q}{r} \cdot \frac{1}{(\sqrt{r^2+ (L/2)^2})} }[/math] where r represents the distance from the rod to the observation location.

Step 4:Checking the Result

Finally, the fourth step is to check the result. The units should be the same as the units of the expression for the electric field for a single point particle [math]\displaystyle{ E = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \cdot \frac{Q}{r^2} }[/math]. Our answer has the right units, since [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{(\sqrt{x^2+ (L/2)^2})} }[/math]. has the same units of [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{Q}{r^2} }[/math] Is the direction qualitatively correct? We have the electric field pointing straight away from the midpoint of the rod, which is correct, given the symmetry of the situation. The vertical component of the electric field should indeed be zero.

The System in Question

As discussed in the previous section, we're considering a system abstracted from the particle model we're familiar with, therefore we will make the generalization that our rod of length L has a total charge of quantity Q. For this generalization, we will need to assume that the rod is so thin that we can ignore its thickness.

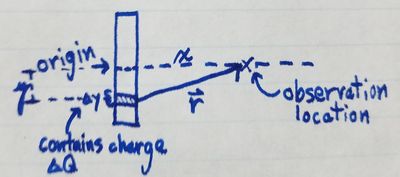

Since the electric field produced by a charge at any given location is proportional to the distance from the charge to that location, we will need to relate the observation location to the source of the charge, which we will consider the origin of the rod. To do that, we will need to divide the rod into pieces of length [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta y }[/math] each containing a charge [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta Q }[/math]. In the image below, you can see what this looks like and the relation that can be found between the observation location and the source, forming the distance vector [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} }[/math].

By the pythagorean theorem, we can find the vector [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} }[/math] as follows:

And to find the unit vector in the direction of [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{r} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{r} }[/math], we do as

follows:

Finding the Contribution of Each Piece to the Electric Field

Now that we've set up a model for the system, with the rod broken down into pieces, we can find the contribution of each piece to the electric field of the system. We will start from the electric field equation you learned for a point particle but plug in the parameters for the rod system into the equation.

By mathematically simplifying, we then get the following equation:

Finding the Net Contribution of all Pieces

In the previous section, we found out the contribution to the electric field at a given location of only one of the pieces constituting the rod. In order to figure out the net field at any particular location, we need to add up the electric fields produced by individual pieces along the length of the rod.

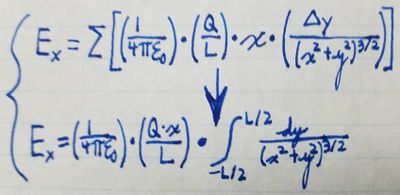

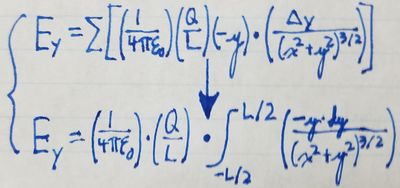

We will switch from vector notation for the electric field to the scalar notation for the x- and y-components. (From the vector in the equation above, we can see that the z-component of the electric field at any point is always 0.) The x-component of the electric field is the sum of the x-components of every [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta{y} }[/math] along the rod, and the y-component of the electric field is the sum of the y-components of every [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta{y} }[/math] along the rod. We can show this mathematically:

To make use of this relation, because we don't know [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta{Q} }[/math], we need to

relate it to parameters that we already know about the rod system we're

analyzing. We can express [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta{Q} }[/math] as the charge density of the rod

(which is Q/L) times the [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta{y} }[/math] we've chosen for the system. Thus,

By plugging the above equation into our equations for the x- and

y-components of the electric field at a point, we can find the electric

field at any point in the system. This technique is called numerical

integration and is typically done by computers because the computational

complexity is dependant upon the size of [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta{y} }[/math] with respect to L.

Simplifying

Using calculus, we can simplify a lot of the math required to compute the electric field at any given point. Notationally, all we're doing is switching from the discretely-sized [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta{y} }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ dy }[/math] and from the sigma notation to an integral starting from -L/2 (the lower end of the rod) and ending at L/2 (the upper end of the rod) as follows:

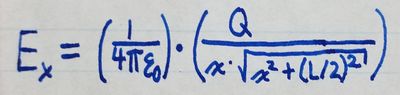

By evaluating the integral, we can determine that the x-component of the

electric field at any point is:

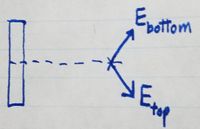

Without evaluating the integral for the y-component of the electric field,

we can use symmetry to determine that the y-component of the electric

field at any given point is 0. Let's consider the contributions to the

electric field from the top and bottom halves of the rod at any

observation point.

Since the y-components of [math]\displaystyle{ E_{top} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ E_{bottom} }[/math] are of equal magnitude and

opposite direction, they cancel each other out, and therefore the

y-component of teh electric field at any given point due to the rod is 0.

Finally, because the rod is round and can be rotated, as a convenience,

we'll use d (distance from the rod) as opposed to x (distance along the

x-direction) to refer to the electric field.

Thus we can simplify electric field calculations for a rod into a form that we can readily use:

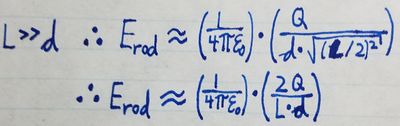

Further Simplification

By noting the contributions of each variable to the equation for the electric field, we can make approximations to simplify our math by simply declaring one variable as insignificant.

For example, if we have a system in which the length of a rod is much greater than the magnitude of the distance from the rod (denoted L>>d), we can neglect some of the instances in which d is taken into account as follows:

A Computational Model

(Finding the Electric Field from a Rod with Code)

Here is some code that you can run which shows the electric field vector at a given distance from the rod along its length. The rod is shown as a series of green balls to help emphasize that when using the numerical integrations mentioned on this page, you are measuring the field produced by discrete parts of the rod being analyzed.

Notice the edge-effects of the electric field of the rod. For reasons discussed above, if we used the long rod approximation (L>>d), these effects would be negligible.

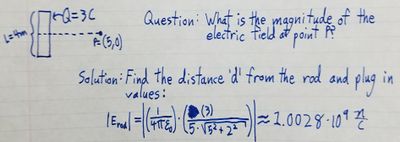

Examples

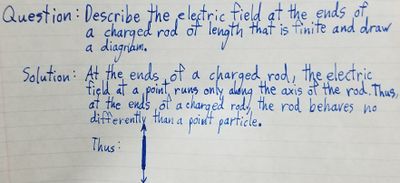

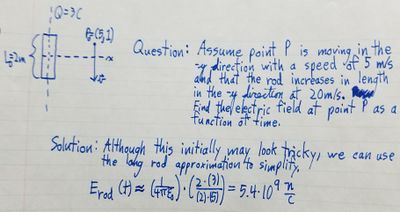

Although this is not a very difficult topic, some reasonably difficult conceptual questions can be asked about it.

Simple

Middling

Difficult

Connectedness

Electric fields are very important to electrical engineering because they can be used to convey signals. In fact, there is an entire sub-field of electrical engineering called digital signal processing that focuses on modulating different characteristics of radio frequency (RF) signals that are produced by electric fields.

History

The history of the electric field can be found in a previous section on electric fields. The equation for the electric field of a charged rod was not a discovery, but simply a mathematical simplification that someone made to model a rod. As such, nobody knows who first made the mathematical simplification, where they made it, or when, though it was certainly made after electric fields were discovered.

See also

The equation for the electric field of a charged rod was derived from the equation for an electric field of a charged particle. See the article "Electric Field" for more information.

Further Reading

The page on electric fields: Electric Field

External Links

http://online.cctt.org/physicslab/content/phyapc/lessonnotes/Efields/EchargedRods.asp

http://dev.physicslab.org/Document.aspx?doctype=3&filename=Electrostatics_ContinuousChargedRod.xml

References

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BBWd0zUe0mI

(For the above reference, I chose to follow the textbook's method in not defining the charge distribution and assuming it was constant, though this was helpful in figuring out a better way to introduce it.)

Chabay and Sherwood: Matter and Interactions, Fourth Edition, Chapter 15

All figures created by author