Atomic Theory: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

Erwin Schrödinger examined the possibility that moving electrons behaved more like waves than particles, and published "Schrödinger's Equation" in 1926. Although this resolved many issues encountered with the Bohr model, it faced opposition from physicist [[Max Born]]. Instead, Born suggested a wave-particle duality of electrons, which stated that electrons could behave both like a wave and a particle. | Erwin Schrödinger examined the possibility that moving electrons behaved more like waves than particles, and published "Schrödinger's Equation" in 1926. Although this resolved many issues encountered with the Bohr model, it faced opposition from physicist [[Max Born]]. Instead, Born suggested a wave-particle duality of electrons, which stated that electrons could behave both like a wave and a particle. | ||

As electrons were now given properties of waves, it was impossible to simultaneously determine an electron's exact location and momentum around the nucleus. Werner Heisenberg, first described this phenomena in 1927, and it was later named the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. This refuted the Bohr model of the atom, and replaced it with a pattern of probabilities as to where electrons are located around the nucleus. These patterns are referred to as atomic orbitals and come in a variety of shapes (basic spheres, rings, dumbbells, etc.) and the nucleus is always at the center. | As electrons were now given properties of waves, it was impossible to simultaneously determine an electron's exact location and momentum around the nucleus. Werner Heisenberg, first described this phenomena in 1927, and it was later named the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. This refuted the Bohr model of the atom, and replaced it with a pattern of probabilities as to where electrons are located around the nucleus. These patterns are referred to as atomic orbitals and come in a variety of shapes (basic spheres, rings, dumbbells, etc.) and the nucleus is always at the center. | ||

[[File:Neon_orbitals.JPG|center|The first five atomic orbitals: 1s, 2s, 2px, 2py, and 2pz.]] | [[File:Neon_orbitals.JPG|thumb|center|The first five atomic orbitals: 1s, 2s, 2px, 2py, and 2pz.]] | ||

==Connectedness== | ==Connectedness== | ||

Revision as of 01:43, 2 December 2015

Claimed by: Caitlyn Caggia (ccaggia3)

Atomic theory states that matter is composed of discrete units, called atoms. The word "atom" comes from the Greek word for uncuttable, atomos. Scientists later discovered that atoms were indeed able to be broken into subatomic, or elementary, particles including protons, neutrons, and electrons. Atomic theory has evolved greatly over time, but the most recent model stems from quantum mechanics.

History

John Dalton: The Law of Multiple Proportions and Atomic Mass

Working from the conservation of mass principle, chemist John Dalton determined the law of multiple proportions to understand how different elements combined in compounds. In 1803, he proposed that each element of the periodic table was composed of identical components, atoms, that were unique to each element. He also suggested that these atoms were not created nor destroyed when one element was combined with another. Dalton's empirical, experimentally-based work marked the first scientific theory of the atom.

Dalton proposed a list of atomic weights in 1805. However, Dalton failed to recognize natural tendencies of elements in nature (for example, oxygen typically exists as a diatomic molecule as [math]\displaystyle{ \text{O}_2 }[/math]). Dalton was unable to distinguish between atoms and molecules (groups of atoms).

Amedeo Avogadro: Avogadro's Law

In 1811, Amedeo Avogadro studied gases and determined that the amount of volume a gas occupies is not determined by the mass of the gas. This allowed Avogadro to take more accurate atomic measurements of gases than Dalton, and differentiate atoms from molecules.

Robert Brown: Brownian Motion

A Scottish botanist, Robert Brown, studied the motion of tiny pollen particles in water in 1827. The particles followed complex paths, dubbed Brownian Motion. As early as 1905, Albert Einstein used Brownian Motion to predict the size of atoms and molecules.

J.J. Thomson: The Plum-Pudding Model and Electrons

Through his work with cathode rays, J.J. Thomson discovered the electron in 1897, and was the first to learn that atoms weren't actually "uncuttable" as initially thought. Thomson knew that atoms had a net neutral charge, but he only knew that negative particles existed. Thus, Thomson developed the "plum-pudding" model of negatively charged electrons floating in a sea of positive charge. (He likened the relationship of electrons to the sea of positive charge to that of plums in plum pudding.)

Ernest Rutherford: Gold Foil Experiment and the Nucleus

In 1909, one of Thomson's students, Ernest Rutherford, determined that the positive charge of atoms was located in a central nucleus. He shot small, positively charged alpha particles at thin sheets of gold foil and noted that some particles were sharply deflected. This deflection could only occur if the positive components of atoms were located in a small area, which Rutherford assumed to be the center. He proposed a planetary model of atoms where a cloud of electrons surrounded a central, positively charged nucleus.

Niels Bohr: Introducing Quantum Physics

As quantum mechanics progressed through the work of Albert Einstein and Max Planck, Niels Bohr updated the atomic model in 1913 to account for quantum phenomena. Bohr, who was also one of Rutherford's students, suggested that electrostatic forces kept electrons in circular orbit around the positively charged central nucleus. In support of his theory, Bohr examined the behavior of electrons in hydrogen molecules and noted that they followed distinct energy levels. When an electron changed energy levels, it gained or lost energy, which could be emitted in the form of light. While the Bohr model holds true for hydrogen, it isn't accurate for multi-electron elements.

James Chadwick: Neutrons

James Chadwick won a Nobel Prize in 1935 for his discovery of the neutron. Starting with Rutherford's work, Chadwick continued experimenting to determine the excess mass in the nucleus that wasn't accounted for by protons. He found that neutrally charged particles, dubbed neutrons, were also inside the nucleus.

The Current Model: Quantum Physics and Electron Orbitals

Erwin Schrödinger examined the possibility that moving electrons behaved more like waves than particles, and published "Schrödinger's Equation" in 1926. Although this resolved many issues encountered with the Bohr model, it faced opposition from physicist Max Born. Instead, Born suggested a wave-particle duality of electrons, which stated that electrons could behave both like a wave and a particle. As electrons were now given properties of waves, it was impossible to simultaneously determine an electron's exact location and momentum around the nucleus. Werner Heisenberg, first described this phenomena in 1927, and it was later named the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. This refuted the Bohr model of the atom, and replaced it with a pattern of probabilities as to where electrons are located around the nucleus. These patterns are referred to as atomic orbitals and come in a variety of shapes (basic spheres, rings, dumbbells, etc.) and the nucleus is always at the center.

Connectedness

While classical physics applies to large objects moving much slower than the speed of light, modern physics deals with special cases of tiny objects, like atoms, subject to relativistic effects. Atomic theory is vital to understanding many quantum physics concepts that are covered in both Physics 2211 and 2212, like the ball-and-spring model of solids, point charges, and conductivity.

Although one can argue physics applies to just about every aspect of life, and atomic theory is critical to understanding physics, atomic theory has directly influenced material science, power generation, electronics, and even food processing, to name a few.

-

Material Science: Synthetic diamonds are used for both cosmetic retail and in manufacturing cutting tools.

-

Power: Solar cells and power rely on the photovoltaic effect and the wave-particle duality of subatomic particles (like photons).

-

Electronics: Silicon, a popular semiconductor used in electronics, is produced industrially in a single-crystal form.

-

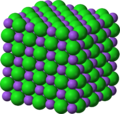

Food processing: An atomic view of table salt. Purple particles are sodium (Na), and green particles are chlorine (Cl).

-

Defense: Nuclear weapons were used during World War II.

-

Medicine: MRI's provide doctors critical information without the risks of surgery.

-

Manufacturing: Many common household items are made with plastic.

See also

Notable Scientists

Related Theories

Concept Application

- Ball and Spring Model of Matter, Ball and Spring Model

- Length and Stiffness of an Interatomic Bond, Young's Modulus

- Density, Charge, Spin, and Conductivity

- The Photoelectric Effect, Photons

- Rest Mass Energy

- Potential Energy of a Pair of Neutral Atoms

External links

- Physics Portal description of Molecular Theory and Subatomic Particles

- HyperPhysics summary of Quantum Physics

- Demonstration of the various models of a hydrogen atom

References

Chapter 30 of OpenStax Textbook

Physics Portal page on Atomic Theory