SI Units

This page describes the International System of Units and lists its units.

The Main Idea

The International System of Units is a set of units allowing for the quantification of each physical dimension. It was invented in France as an extension of the metric system under the name "Système Internationale d'Unités," which is why it is abbreviated to "SI". SI Units are practically universally used for scientific applications, and are used in most countries in everyday life as well, although the United States, which uses customary units, is a notable exception. Most of quantities in this course will be given in SI units.

The International System of Units has seven base units with specific definitions and countless derived units which are created by multiplying and dividing the base units. For example, the meter (m) is the base unit for the dimension distance and the second (s) is the base unit for the dimension time. The meter per second (m/s) measures the dimension speed and is a derived unit because it can be obtained by dividing the meter by the second.

Because measurements must often be made on many different scales, the International System of Units also defines a variety of prefixes for use with its units. The prefixes scale the values of each unit by powers of 10.

The International System of Units is versatile and can change over time to meet the evolving needs of scientists. Over the last several centuries, the number of base units has grown from 3 to 7 as a result of the discovery of new dimensions that could not be expressed in terms of existing base units. The number of derived units recognized as meaningful has also grown substantially and will likely continue to as the human understanding of the physical world improves. Additionally, the seven base units have undergone redefinition at several points in time, most recently on May 20 2019. The purpose of each redefinition is not to change the units' values (in fact, their values are changed as little as possible), but to make their definitions more universally constant and reproducible.

The Seven Base Units

The values of the seven base units are historically motivated, but most of their current definitions have been changed from the original. Today, each of the 7 base unit is defined by fixing a specific natural universal constant at a certain numerical value.

Second (s)

The second measures time.

Today, the second is defined by fixing the value of the cesium hyperfine transition frequency [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta v_{Cs} }[/math] at exactly 9192631770 hz (transitions per second). This defines the second as the 9192631770 times the period of the transition between the two levels of the ground state of cesium-133 atom. Atomic clocks make use of this phenomenon by counting the cesium transitions as a mechanism for keeping time! This definition was instated in 1967.

The second was initially defined as a fraction (1/86400) of a day of 24 hours of 60 minutes of 60 seconds. This definition is poor primarily because the duration of the day changes slightly over time. In 1956 the second was defined as 1/31556925.9747 of the tropical year. (The tropical year is the time it takes the sun to return to the same position in the season cycle, which is about 20 minutes shorter than the causal year.) However, this is still not as elegant as the current definition because it is based on our particular solar system, which may not always exist or be available for measuring.

Meter (m)

The meter measures distance.

Today, the meter is defined by fixing the value of the speed of light in a vacuum [math]\displaystyle{ c }[/math] at exactly 299,792,458 m/s. Since the second is already defined, this defines the meter as the distance traveled by light in a vacuum in 1/29979248th of a second.

The meter was originally defined in 1973 as 1/10,000,000 of the meridian through Paris between the North Pole and the Equator. In 1960 it was redefined as 1650763.73 wavelengths of the radiation in a vacuum corresponding to the transition between 2p10 and 5d5 transition levels of the krypton-86 atom.

Kilogram (kg)

The kilogram measures mass.

Today, the kilogram is defined by fixing the value of Planck's constant [math]\displaystyle{ h }[/math] at exactly 6.62607015×10−34 J s. Recall that the joule is not a base unit, but a derived unit equal to the kg m2/s2. Since the meter and the second are already defined, this leaves only one possible value for the kilogram. This definition was instated as part of the SI unit redefinition of May 20, 2019.

In 1973, the SI unit for mass was called the grave. It was defined as being the mass of 1 liter of pure water at its freezing temperature. Later, in 1889, it was redefined as the mass of a specific sample a platinum alloy. The sample is called "Le Gran K" and is kept in a temperature-controlled vault just outside of Paris, France. This definition was inadequate because it was not universally reproducible.

Ampere (A)

The ampere measures electrical current.

Today the ampere is defined by fixing the value of the elementary charge [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] at exactly 1.602176634e-19 C. This defines the Coulomb, and since an ampere is 1 Coulomb per second (and the second is already defined), it also defines the Ampere.

In 1881, the ampere was defined as a tenth of the current required to create a magnetic field of one Oersted at the center of a 1cm arc of wire with curve radius 1cm. In 1946, the ampere was defined as the current required to create a force of 2e-7 Newtons per meter of length between two straight parallel conductors of infinite length placed 1m apart in a vacuum.

Kelvin (K)

The Kelvin measures temperature.

Today, the Kelvin is defined by fixing the value of the Boltzmann constant [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] at exactly 1.380649 x 10–23 J/K. Since the joule is a derived unit derived from the second, the meter, and the kilogram, each of which has already been defined, this leaves only one possible value for the Kelvin.

Mole (mol)

The mole measures the amount of a substance present by number of particles.

Today, the mole is defined by fixing the value of the Avogadro constant [math]\displaystyle{ N_A }[/math] at exactly 6.022140857 × 1023 mol-1. This defines the mol to be 6.022140857 × 1023 mol particles.

The mol was originally defined in 1967 the mole as the number of carbon-12 atoms necessary to comprise a 12 gram sample.

Candela (cd)

The candela measures luminous intensity.

Today, the candela is defined by fixing the value of the luminous efficacy constant [math]\displaystyle{ K_{cd} }[/math] at exactly 683 lumens per watt. This defines the candela as the luminous instensity of a source that emits radiation of a frequency 5.4e14 Hz in 1/683 of a steradian. (A steradian is the 3D analog for the radian; it is a part of the sphere's surface area equalling the radius squared in area.) This is about the luminous intensity of a candle.

Derived Units

There are many useful quantities in physics that cannot be measured in a single base unit. These must be expressed in derived units, which are obtained by multiplying and dividing the base units. For example, the meter (m) is the base unit for the dimension distance and the second (s) is the base unit for the dimension time. The meter per second (m/s) measures the dimension speed and is a derived unit because it can be obtained by dividing the meter by the second. Speed does not get its own base unit because it does not need one; speed is fundamentally a relationship between distance and time (specifically, distance traveled and the time it takes to travel that distance). Other examples of derived SI units are the kg/m3, which measures density, and the kgm/s, which measures momentum.

Some derived units are used so frequently in physics that they are given their own names. Below are several such derived units:

| Unit | Symbol | In Terms of Base Units | Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| hertz | Hz | [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{s}^{-1} }[/math] | frequency |

| newton | N | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\mathrm{kg}\mathrm{m}}{\mathrm{s}^2} }[/math] | force |

| pascal | Pa | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\mathrm{kg}}{\mathrm{m}\mathrm{s}^2} }[/math] | pressure |

| joule | J | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\mathrm{kg}\mathrm{m}^2}{\mathrm{s}^2} }[/math] | energy |

| watt | W | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\mathrm{kg}\mathrm{m}^2}{\mathrm{s}^3} }[/math] | power |

| coulomb | C | [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{As} }[/math] | charge |

| volt | V | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\mathrm{kg}\mathrm{m}^2}{\mathrm{A}\mathrm{s}^3} }[/math] | electric potential |

This list is not comprehensive, and there are many unnamed derived units that are commonly used as well.

Prefixes

Because measurements must often be made on many different scales, the International System of Units also defines a variety of prefixes for use with its units. The prefixes scale the values of each unit by powers of 10. For example, the kilometer is 1000 times as long as the meter because of the prefix "kilo." The use of prefixes allows even large and small measurements to be reported with reasonable and easy to read numbers. For example, it is easier to express the atomic radius of the hydrogen atom as 53 picometers than 5.3 x 10-11 meters.

Each prefix has a symbol, which can be combined with the symbol of a unit. For example, the symbol for pico is "p", so "pm" is the symbol for picometer.

The following table shows the common prefixes used with SI units.

| Prefix | Symbol | Multiplier |

|---|---|---|

| peta | P | 1015 |

| tera | T | 1012 |

| giga | G | 109 |

| mega | M | 106 |

| kilo | k | 1000 (103) |

| hecto | h | 100 (102) |

| deka | da | 10 (101) |

| deci | d | .1 (10-1) |

| centi | c | .01 (10-2) |

| milli | m | .001 (10-3) |

| micro | [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math] | 10-6 |

| nano | n | 10-9 |

| pico | p | 10-12 |

| femto | f | 10-15 |

There are several popular mnemonic devices for remembering some of the prefixes. A common example is "King Henry Died by Drinking Chocolate Milk." The first letter of each word represents a prefix, starting at kilo and ending at mili. The "b" in "by" stands for "base unit," which in this context means a unit with no prefixes.

Dimensional Analysis

Dimensional analysis is the analysis of the units used in expressions and equations. Dimensional analysis revolves around the fact that when two quantities, each measured with a specific unit, are multiplied or divided, their units are multiplied or divided as well. For example, consider car traveling in a straight line at a constant speed of 20m/s. Suppose you want to know how far it travels in 30 seconds. To calculate the answer, simply multiply 20m/s by 30s, which is 600m. Notice that the meter per second times the second equals the meter.

A result of the above rule is the fact that both sides of an equation must have the same units. This makes sense because two quantities in different dimensions can't be compared. To illustrate this fact, consider the ideal gas law:

[math]\displaystyle{ PV=nRT }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] is the pressure of the gas, [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math] is its volume, [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] is the number moles of the gas, [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] is the ideal gas constant, and [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math] is the temperature of the gas.

For the ideal gas law to be numerically true, the ideal gas constant [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] must be in the correct units. The SI units for pressure, volume, and temperature respectively are the kilopascal (kPa), the cubic meter (m3), and Kelvin (K). If these units are used, [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] must be given in m3 kPa / mol K. That way, both sides of the equation are in m3 kPa. R can also be given in other units, as long as they are a unit of volume times a unit of pressure divided by moles and a unit of temperature. Its value depends on the units used. In fact, all natural constants can have different values depending on the units in which they are given. In this class, they are typically given in their SI units.

All equations in physics, like [math]\displaystyle{ PV=nRT }[/math], are true for all units, as long as their two sides agree in units, which requires the correct versions of any natural constants. Generally, SI units are preferred.

The fact that both sides of an equation must have the same units can be useful for determining the units of a quantity, or, if the units of all quantities are known, for verifying that a derived equation makes sense and is possible.

Unit Conversion

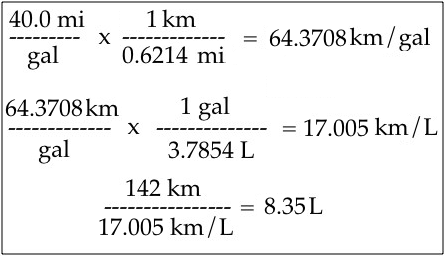

Measured quantities can be converted from one unit to another as long as the relationship between the two units is known. To do so, the quantity should be multiplied by the ratio of the two units' values, with the quantity's current unit in the denominator and the target unit in the numerator. For example, suppose you want to convert 7cm to inches, given that an inch is equivalent to 2.54cm. 7cm should be multiplied by the ratio of the inch to the centimeter, which is [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1\mathrm{in}}{2.54\mathrm{cm}} }[/math]:

[math]\displaystyle{ 7\mathrm{cm} * \frac{1\mathrm{in}}{2.54\mathrm{cm}} = 2.76\mathrm{in} }[/math].

Examples

Connectedness

This topic can be applied to every aspect of science. When solving the problem, or even when doing research, every equation and theory is based on SI units. It is a promise between scientists that they will use these certain units to reduce errors or misunderstanding. Therefore, it is very important to know the concept of SI units. This topic is connected to not only physics but also every other scientific subject. In addition, it might not be familiar in the United States, but in most other countries, they use SI units in ordinary life. SI units create a form of standardization throughout the scientific community. This standardization stems from their connection to fundamental constants. These constants are dependent on naturally occurring laws on Earth. As a result, since these units are connected to these constants that are unchanging no matter what location on Earth they're being observed at, this system of measurement is able to achieve a high level of standardization. This establishes a sense of unity and allows scientists to be on the same page no matter what nationality they are. It's through the use of these units by the community of scientists as a whole that error can be reduced to a minimum and calculations and findings can be standardized across the globe. SI units also allow scientists to reproduce experiments and record their results in the same form. This allows for more credibility among findings as well. SI units are also very useful for the use of dimensional analysis. Dimensional analysis is the mathematical problem solving method that essentially means that any number expression can be multiplied by another and its inherent value won't be changed. This vital problem solving idea is possible due to the fact that SI units can be converted to non SI units with incredible ease. SI units create an incredible amount of standardization throughout the scientific community and have been essential for the production of viable and credible scientific results.

Due to recent events in the scientific community and the new levels of accuracy achieved from the use of modern and scientifically advanced equipment, there have been several discoveries that can redefine how we understand fundamental constants. Since SI units are closely intertwined with fundamental constants, these discoveries have great relevance. Most of these discoveries are in the field of quantum physics which is a new field in comparison to other scientific subjects. The technology age has given scientists cutting-edge equipment allowing them to reach results that are more specific and accurate than ever before. For example, this equipment can allow them to calculate a more accurate mass of an electron, which is an important constant and affects the values of base units in the SI unit system. When discoveries like these directly affect our understanding of fundamental constants, they can have an effect on the SI unit system. However, some discoveries, but not all, might only change the value of a constant by a minuscule amount, so the SI units will barely change their values and will most likely not directly affect the way most students solve problems since they will tend to round in problems.

History

The Metric System was created around the time of the French Revolution and the subsequent deposition of two platinum standards representing the meter and the kilogram, on 22 June 1799, in the Archives de la Republic in Paris can be seen as the first step in the development of the present International System of Units. Each of the base units has root within the physical world. For example the unit of metre is derived from dimensions of the Earth, the kilogram was derived the volume of of one liter of water. These 2 units are the baseline for the remainder of the SI system. The new metric system was originally abandoned by France. In 1837, the metric system was readopted by France, and slowly then became adopted by the scientific community. After this a man named James Clerk Maxwell presented the idea of a number of base units, time, mass, and length. This 3 base units could then be used to derive a series of other measurements throughout the scientific world. However it was quickly discovered that these units cannot describe non-mechanical properties. Most importantly they couldn't properly describe the electrical properties of the world. A man named Giovanni Giorgi, an Italian physicist and electrical engineer, proposed a fourth base unit should be added to the original 3 in order to properly describe the electrical systems of the world. This unit was later decided, in 1935, to be the ampere thus allowing the world to aptly describe electrical systems as well. As the years passed these units began to become more and more commonplace among the world, with many other countries beginning to use the SI system as their main form of measurement. The SI system quickly became the accepted scientific measuring system as well. The use of this system has helped to advance and drive scientific advancement throughout the years.

Furthermore, the SI unit system was established in 1960 by the 11th General Conference on Weights and Measures. The CGPM is the international authority that ensures wide spread of the SI system, and it modifies the SI system as necessary to reflect the latest advances in science and technology. The General Conference receives the report of the International Committee for Weights and Measures on work accomplished. It discusses and examines the arrangements required to improve the International System of Units (SI). It also then endorses the results of new fundamental determinations and various scientific resolutions and applies them to an international scope. It further decides all major issues concerning the development of the organization as a whole.

See Also

Further reading

SI Units for Clinical Measurement 1st Edition by Donald S. Young

Matter & Interactions, Vol. I: Modern Mechanics, 4nd Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood (John Wiley & Sons 2015)

Base units of the SI, fundamental constants and modern quantum physics by Christian J Bordé

External Links

http://physics.nist.gov/ National institute of standards and Technology.

http://wps.prenhall.com/wps/media/objects/165/169061/blb9ch0104.html Pearson educational site.

Matter & Interactions, Vol. I: Modern Mechanics, 4nd Edition by R. Chabay & B. Sherwood (John Wiley & Sons 2015)

Tutorial & Drill Problems for General Chemistry (and Intro) By Walter S. Hamilton, Ph.D.

Base units of the SI, fundamental constants and modern quantum physics By Christian J Bordé, Published 15 September 2005

https://www.youtube.com/embed/h04x3Vr2GGE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZMByI4s-D-Y

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_e1wITe_ig&t=521s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YmCrFPC1qi4

https://www.bipm.org/en/measurement-units/