James Chadwick

Claimed by Natalie Payne (npayne7)

Sir James Chadwick (1891-1974) was an English physicist and diplomat, best known for winning the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for discovering the neutron. He also wrote the Military Applications of Uranium Detonation (MAUD) report, which led the US government to realize the potential of nuclear weapons and to begin serious research into the subject. He was the head of the British group that worked on the Manhattan Project, which resulted in the production of the first atomic bombs. He was knighted in 1945 by King George VI for his contributions to science. In 1946, he was appointed the British advisor to the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission. Later in life, he continued to work in academia as the Master of of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. During his tenure, the academic reputation of the college increased dramatically, and he retired from this position in 1959. He passed away in his sleep on July 24, 1974 at the age of 82.

Early Life and Education

James Chadwick was born on October 20th, 1891 in Bollington, Cheshire, England. He was the eldest child of Joseph Chadwick and Mary Knowles. His parents moved to Manchester, England in 1894 while he remained in Bollington with his grandmother. He joined his parents in Manchester at age 11 while attending the Central Grammar School for Boys. After graduation from secondary school in 1908, he matriculated at the Victoria University of Manchester. He intended to study mathematics, but he enrolled in the physics program by mistake, and he graduated from the university's Honours School of Physics in 1911. His next two years were spent at the Physical Laboratory in Manchester working on various radioactivity problems under Ernest Rutherford, and he earned a M.Sc in 1913.

Research

Germany

In 1913, he was awarded the 1851 Exhibition Scholarship to be able to move to Berlin and study at the Physikalisch Technische Reichsanstalt under Hans Geiger. There he studied beta radiation, and with the help of the newly invented Geiger counter, Chadwick was able to demonstrate that beta radiation produces a complete (continuous) spectrum and not just spectral lines as previously thought. He was still in Berlin at the time of the outbreak of World War I, and was interned at the Ruhleben internment camp for the duration of the war. After his release, he accepted the Wollaston Studentship at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, and moved back to England in 1919

Cambridge

While at Cambridge, Chadwick continued to work under Rutherford who was the newly appointed head of the Cavendish Laboratory. In 1919, Rutherford succeeded in disintegrating atoms by bombarding nitrogen with alpha particles, with the emission of a proton, which was the first artificial nuclear transformation. Together, Chadwick and Rutherford continued this work by accomplishing the transmutation of other light elements by bombardment with alpha particles, and by studying the properties and structure of atomic nuclei. At the time, it was believed that the nucleus of an atom contained protons and electrons, but the concept of spin created anomalies in the model. Atoms had the right atomic number but the wrong spin. This led Chadwick and Rutherford to hypothesize the existence of another subatomic particle. In 1932, Walter Bothe and his student Herbert Becker used polonium to bombard beryllium with alpha particles, and this produced a new, unusual form of radiation. It was initially believed that this was to be gamma radiation, because the rays were neutral, because they did not deflect when passed through a magnetic field and extremely penetrating. Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie discovered that when a beam of the radiation hit a proton-rich substance like paraffin, protons were knocked off. The Joliot-Curies believed that this was gamma radiation, but Chadwick and Rutherford disagreed because they believed that protons were too heavy for this to occur. Chadwick then designed an experiment to test for the presence of neutrons. The apparatus consisted of a cylinder of polonium aimed at a piece of beryllium. The resulting radiation was then directed towards a piece of paraffin, and the displaced protons from the paraffin were measured with a Geiger counter.

In February 1932, after only weeks of experimenting with neutrons, Chadwick announced his findings in the letter to the editor of Nature. He officially published his work in May 1932, with the article titled "The Existence of a Neutron". With Chadwick's discovery, Heisenberg proposed the proton-neutron model for the nucleus. Rutherford believed that a neutron was just a proton-electron pair, but Heisenberg demonstrated that there were no electrons present in the nucleus. In 1935, Chadwick won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron (read his Nobel lecture here)

Liverpool

In 1935, months before he was awarded his Nobel Prize, Chadwick was offered the Lyon Jones Chair of the School of Physics at the University of Liverpool. He wanted to start a nuclear physics research group at Liverpool, but the laboratories were so outdated (they still ran on direct current electricity) that this wasn't possible. He was instrumental in renovating the labs to a modern state, and he used some of his own Nobel Prize money to procure a cyclotron (particle accelerator) for the university.

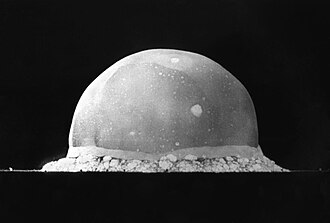

In 1939, the British government asked Chadwick to begin research into nuclear weapons. Despite the difficult working conditions due to the air raids on Liverpool, by spring of 1941 his group had determined that the critical mass of uranium-235 for a nuclear detonation was about 8 kg. In the summer of 1941, Chadwick wrote a report that summarized all of the nuclear weapon research done in the UK, called the Military Applications of Uranium Detonation (MAUD) report. President Roosevelt read this report, and soon after, the US government began the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb. From 1944 to 1946, Chadwick and his family lived at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico so he could oversee the British group working on the Manhattan Project. He was present at the Trinity nuclear test on July 16, 1945 when the world's first atomic bomb was detonated (watch a video of the Trinity detonation here)

Later Life

He was knighted in 1945 by King George VI for his contributions to physics. After the war ended, he was appointed to the the UK Advisory Committee on Atomic Energy (ACAE) and the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission. In 1948, he accepted the position of Master of Gonville and Caius College, where he did his Ph.D. The academic reputation of the college increased dramatically during his Mastership, due to the increase in the number of research fellowships and the hiring of controversial faculty. It was during his tenure that Francis Crick and James Watson discovered the double helix structure of DNA. He remained in this position until his retirement in 1959. He passed away peacefully in his sleep on July 24, 1974 at his home in Cambridge.

Legacy

The discovery of the neutron lead to the development of the model of the atom as we study it today. This transformed subatomic physics and chemistry, allowing scientists to discover new elements. It also lead to the discovery of nuclear fission, which has been used in war (for weaponry) and peace (nuclear reactors). The process of nuclear fission has had some major consequences since the first atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, including the Chernobyl and Fukushima nuclear disasters, which have had a lasting impact on humanity. Without James Chadwick, this groundbreaking process would never have been utilized.

Further Reading

Brown, Andrew.The Neutron and the Bomb: A Biography of Sir James Chadwick (1997). Oxford University Press.

Chadwick, James (1932)."The Existence of a Neutron" Proceedings of the Royal Society A 136(830): 692-708.PDF